This is a guest post provided by Saraf Ali, a resident of Kashmir wishing to inform the outer world of how he and his fellow Kashmiris are faring during these harsh times of lockdown and high-speed internet ban in their region.

We’re Kashmiris, we know to tackle lockdown by birth, beforehand.

Being outdated is known to be the main phenomenon of stopping developments taking place. Outdated communities of underdeveloped countries are regarded to be living in those parts of the country that lack almost all kinds of services and, even worse, basic needs. Information society should be maintained because information has a significant impact on ensuring development in communities but this is not the case here in Kashmir because of information poverty caused by lack of means to access it.

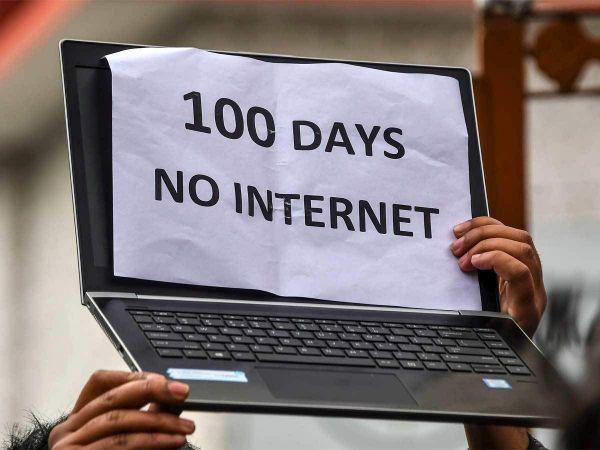

As Covid-19 has unified the world to fight the spread of the deadly infection, virtually, Kashmir still lags far behind and is quite outdated due to a lack of high-speed internet services.

In August 2019, India’s government revoked Kashmir’s special autonomous status and locked down the region, which has a population of around 9 million. According to a September 6 report of the Indian government, nearly 4,000 people have been arrested in the disputed region. Among those arrested were more than 200 politicians, including two former chief ministers of Jammu and Kashmir (J&K), along with more than 100 leaders and activists from All Parties Hurriyat Conference.

The lockdown was followed by the democratic world’s longest internet shutdown, which was partially lifted on Jan. 25 when authorities restored access to 2G internet. But the denial of high-speed internet still prevents people from using banking apps, paying their bills, and accessing services—even forcing some out of their homes. According to the Software Freedom Law Center, the internet in Kashmir was blocked at least 180 times from 2012 to 2019.

The latest bout of violence, however, hasn’t been reported here in Kashmir for months, at the time of the writing. Repeated bans on means of communication, in the hope of restoring so-called peace and normalcy in the Kashmir Valley, is what the government has been defending itself with ever since.

A psychiatrist reports that sitting idle at home together for months diminishes creativity. Here is the same with our students: they’re idle with nothing much to do; neither have they any online classes to attend, nor they’re left with some Netflix things to watch, and spending time playing is not even an option. And it has been more than seven months for students to stay home after the government of India locked down the region to prevent protests against the abrogation of Article 370 in August 2019. The loss could have been compensated by online classes. But here all of us fail to find logic in restricting the internet when everything is fine. “We don’t want schooling to be affected but nobody is paying heed to our pleas,” says Var, private school association Jammu and Kashmir’s president, who has highlighted the issue with authorities to no avail.

Talking about the health sector here in the valley, as posted by the so-called caretaking government is worth naught. The doctor-to-patient ratio in the state is amongst the lowest in India. Compared to the doctor-patient ratio of 1:2000 in India, J&K has one allopathic doctor for 3,866 people, against the WHO (World Health Organization) norm of 1 doctor for 1,000 population, says a survey.

Medical institutions have described the 4G ban as a risk factor for COVID-19 deaths in J&K, as the information about WHO’s guidelines on testing and its countermeasures remains inaccessible in the region. Amnesty International also urged the government to restore 4G internet in the critical situation of the pandemic. Jammu and Kashmir doctors stated that “We’ll die like cattle”. Doctors, according to news media, are not able to deal with the coronavirus due to the non-availability of 4G internet and insignificant information available online. They have clearly expressed their inability to download and access journals and other important information that can prove cardinal in their effort to treat and contain this virus. “This is so frustrating… trying to download the guidelines for intensive care management as proposed by docs in England… 24 Mbs and one hour… still not able to do so”, a professor of surgery here in Government Medical College Srinagar, tweeted.

So now, in light of the many problems faced by local people in the Kashmir Valley, it becomes the duty of the government to restore the 4G mobile services at the ease. 2G connections are however restored and the same should be done with the 4G. It is high time for the government to think about the 9 million people sailing amidst the lockdown without accessible info to keep themselves safe, a way to communicate with their loved ones, and tools for students to carry on with their careers.

Saraf Ali is a freelancer, author, publisher, and first Kashmiri to win a reader’s choice award, persuing engineering in computer science in SSM college of Engineering and technology, Kashmir, can be reached on [email protected].