The road was empty, and the quiet reinstated when I got up at dawn and settled on the bench for my coffee. The sublime landscape of the Lebanese mountains looked different today. It bore the transcendent quality of an exhilarating experience the moment before it wanes into a memory. I regarded it with a tad of anticipatory wistfulness as I mulled that this thrilling trekking adventure had just finished.

Sophie had a flight to Istanbul to catch tomorrow in Beirut. She was going back to work and needed to settle somewhere. I had a couple more weeks to keep exploring Lebanon. One option I’d been pondering was to carry on hiking alone until the trail’s end in the far north. By then, however, I had decided to instead return to civilization and travel to other parts of the country by public transport. So the immediate plan was to somehow get to Tripoli city.

When the morning traffic commenced, we took post on the roadside—Sophie showcased in the front and me lurking in the background: the couple’s optimal hitchhiking practice—and waited for a willing driver. Given the generally accommodating disposition of the Lebanese people, I had expected it to be faster. Still, twenty minutes wasn’t to be complained about.

The Good Samaritan was a young, chummy, intelligent man from a nearby village. An agronomist, he was commuting to the company he worked for in the city. His English was proficient, and we had an interesting chat while we rolled down the mountains toward the coast. He dropped us off in the parking lot of his office block, next to a hectic thoroughfare in the heart of Lebanon’s second-largest metropolitan area.

This story is an excerpt from my book "Backpacking Lebanon", wherein I recount my one-month journey around this fascinating country. Check it out if you like what you're reading.

No sooner did we open the door of the air-conditioned car than a sweep of insane torridity struck us like a fire blast. Amid an exceptional heatwave that during those days engulfed the entire northern hemisphere, if the mountains had felt hot, the Lebanese coast felt like hell. Dripping sweat before even taking a step, we began walking the four kilometers to our accommodation.

Besides the temperature, everything about our new environment felt more oppressive. Gone were the beautiful sceneries, the stillness mixed with bird songs and soft breeze swish, and the rich aromas of nature. So abruptly, they got replaced by dilapidated, bullet-ridden jumbles of cement, the throbbing buzz of urban commotion, and the nauseous fetor of trash heaps.

Our Airbnb was in Mina: the predominantly Christian, oldest district of Tripoli. Our host—a Switzerland-based, English-speaking member of the family that owned the building—didn’t answer our calls and messages upon our arrival at the pre-arranged check-in time because, as we found out three hours later, he was out partying last night and overslept.

The African maid he dispatched downstairs to open the door guided us five floors up and showed us to our flat. It was spacious, bright, neatly furnished with vintage pieces, and had a balcony looking down to a park, the port, and a horizon half occupied by mountains and half by the Earth’s curvature. Most critically, it had AC. All that, combined with its bargain price and the family’s affable demeanor, duly compensated the wait.

After long longing, we experienced this magical moment of a shower that felt as satisfying as hosing down a muddy tile floor. It was followed by an equally satisfying spell of lying below the wheezing AC, postponing the time we ventured out for our skin to feel analogous to a window cleaned during a sandstorm.

We hastened along the sun-baked main road and took the first turn into the shady backstreets. They were a maze of narrow paths meandering through a mishmash of crumbling houses. Colorful clotheslines, in contrast to weeds on the walls, were the only clue to tell the inhabited apart from the uninhabited ones. Their structural condition was practically the same. The combined smell of untreated waste and decayed building materials gave the place a tang of extreme poverty.

The bounded quarter of downtown Mina was in decent shape. Its small traditional houses were well-preserved and its cobbled streets were clean. The main street featured several youth-inundated, hipstery bars and coffee shops. We sat in one’s shaded and fanned garden for lunch before retreating to our flat to wait out the sun.

We went out again to enjoy the sunset over a stroll along the wide promenade that skirted Mina’s coastline. A great share of the city’s population was doing the same. Like in Beirut, there were street vendors of anything imaginable, hookah-smoking companies of young males, and adult family members pursuing kids that raced ahead on bicycles and ride-ons. In addition—something I didn’t observe in Beirut—here there also were teenage boys rocketing wheelied motorbikes through the crowd and endangering the public safety.

After nightfall, we had a drink in the lively pub street and a seafood wrap in the little restaurant on the ground floor of our building. And then we cherished the rejuvenating experience of sleeping in a bed for the first time in ten days.

Then broke the day of Sophie’s departure. We spent a restful morning at home, and after she finished packing, we headed out to the scorched city.

On our way to the main road through Mina’s ramshackle neighborhoods, we got accosted by a gang of a dozen gamins. They had a whale of a time practicing their English with us. For my part, I didn’t find the situation as amusing because they knew and echoed only three English words: money, dollar, euro. That was the most intense begging bout I’ve ever been subjected to outside of Africa. It took the combined scolding of several grown bystanders for them to heed and leave us in peace.

Stopping for an exquisite meal at a traditional Levantine restaurant, we reached the main road. I helped Sophie catch a tuk-tuk to the bus station, and I remained alone with a tinge of renewed loneliness.

I spent most of the day at home, planning my trip’s solitary continuation, and went out late in the afternoon. Being solo felt different not only inward but also with regard to the locals’ attitude toward me. As long as my camera didn’t hang from my shoulder, I blended well into the population and went by unnoticed. Agreeable as it is to attract everyone’s positive attention, I relished the respite from it and the ability to observe from the obscurity of indifference.

A long walk around Mina led me to the pub street by sundown. I drank a beer and went for dinner in a poky restaurant on whose window I had yesterday noticed a Greek flag. As expected, the owner was Greek. Although third generation, he retained a good grasp of the Greek language and seemed exhilarated to receive one of his compatriots. We had a pleasant chat while I was all over the two chicken-liver sandwiches he prepared for me.

Sleeping and waking early, I was out by sunrise for a little sightseeing excursion to uptown Tripoli. The streets were still vacant. I had to walk a few blocks to spot the first tuk-tuk. The driver was ebullient and very talkative. He said he was an army officer and drove the tricycle as a side hustle. Not that I had a reason to doubt him, anyway—he was beefy, buzz-cut, and mustached—but his claim got all the more corroborated when we reached my destination and he seemed to know all the many soldiers manning an entire column of armored vehicles stationed there.

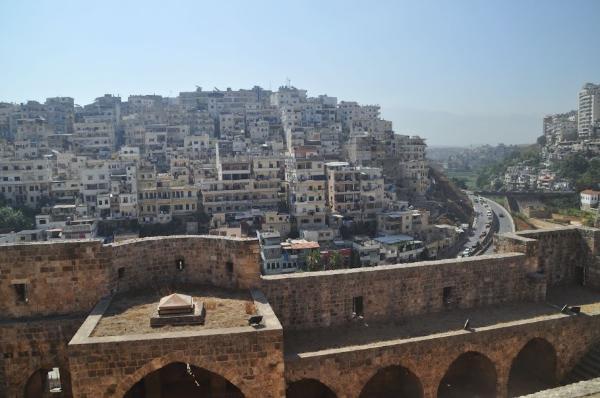

My destination was the Citadel of Tripoli: a massive, conspicuous fortress built by the Crusaders atop a hill overlooking the Qadisha River. It now remained a lone testimony to a distant past, enveloped by one of the densest population centers in the Middle East. The river below was reduced to a waste-ridden sewer, and the surrounding hills were covered by derelict concrete condos from foot to peak.

The historical site was just opening. I was the day’s first visitor. A single worker was present before the fort’s entrance, sweeping rubbish and watering the rarity of a grass patch. A handful more staff loafed at the shaded arcade past the gate, sat on wooden stools and drinking coffee.

One of them, a middle-aged woman, turned out to be Greek: a third-generation descendant of Alexandrian Greeks who immigrated to Lebanon after Nasser kicked them out from Egypt. Although this wasn’t part of her duties, she volunteered to give me a tour around the castle. Filling up with French wherever she missed the Greek words, she chronicled the citadel’s history. It boiled down to a long succession of new masters constructing additions after killing the previous masters.

She guided me everywhere, including a little museum that was presently inaccessible to the public, except for the lower dungeons where she wouldn’t go for her fear of snakes. She advised me against going on my own either, but she showed me the way since I insisted. It was a steep spiral staircase that led me to a maze of passages, rooms, doors, and stairs beneath the castle. I saw no snakes. To be fair, I saw nothing but the ground under each of my landing steps that my phone torch could illuminate.

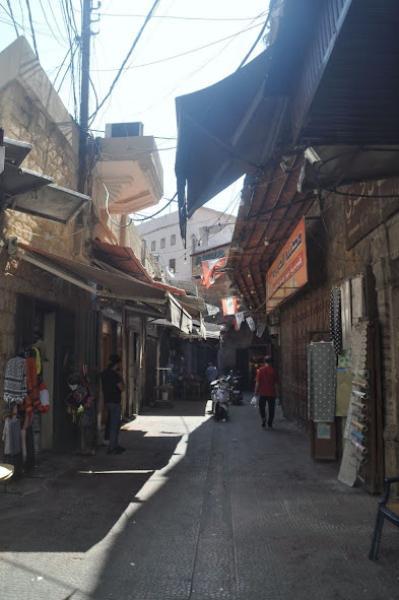

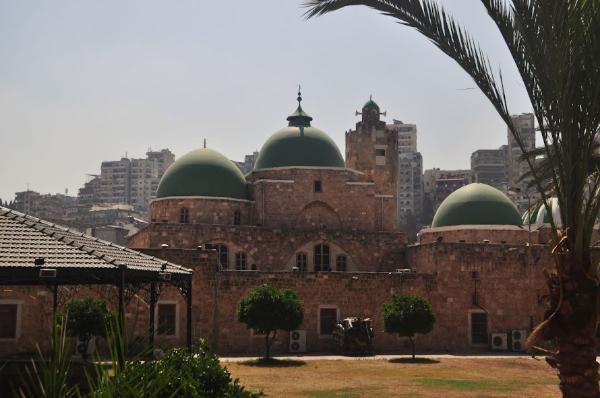

The day’s second visitors arrived just as I was leaving. I descended the hill on foot to continue with a wider exploration of Tripoli. I visited some of the city’s old mosques and souks. The latter were unusually quiet for what you expect across the Arab world. Most shops were closed, and there were so few people that you could walk in a straight line. I don’t know if that was due to the early hour or the economic crisis.

When the heat mounted above tolerable levels, I quit my walk at a traditional cafe. I then grabbed a kebab and bought some tobacco, took a tuk-tuk back home, and spent there the rest of the day, ready to depart in the morning for my next destination.

Photos

View (and if you want use) all my photographs from Tripoli and Mina.

Accommodation and Activities in Lebanon

Affiliation disclosure: By purchasing goods or services via the links contained in this post, I may be earning a small commission from the seller's profit, without you being charged any extra penny. You will be thus greatly helping me to maintain and keep enriching this website. Thanks!

Stay22 is a handy tool that lets you search for and compare stays and experiences across multiple platforms on the same neat, interactive map. Hover over the listings to see the details. Click on the top-right settings icon to adjust your preferences; switch between hotels, experiences, or restaurants; and activate clever map overlays displaying information like transit lines or concentrations of sights. Click on the Show List button for the listings to appear in a list format. Booking via this map, I will be earning a small cut of the platform's profit without you being charged any extra penny. You will be thus greatly helping me to maintain and keep enriching this website. Thanks!