In our age of free and wide distribution of information, it saddens me to observe how poor the average person’s understanding of history is. A century and a half after Tolstoy offered the world his War and Peace masterpiece, many people still see human history as a sequence of heroic and villainous actions performed by extraordinary individuals. As long after Darwin published his On the Origin of Species, still many others view history as a divine qualification test for entry to paradise.

Our historic conception ought today to be better than that. It only takes a little reading and thinking to understand that no gods, no heroes, and not even humans themselves, played any significant role in the unfolding of the grand events that shaped contemporary reality. On the grand scene of history, we are only actors and not playwrights. In this article, I aspire to show not only that geography influenced human history, but rather that it dictated it in the most conceivably direct fashion.

I am fully aware that the strictly deterministic view of history I will here advocate is going to make many people feel very uncomfortable. But bare with me, because, regardless of how depressing and nihilistic this no-free-will perspective may seem at first glance, towards the end of this article, I will be briefly touching on the subject of future history, wherein I believe life will transcend not only geographical boundaries but all physical ones indeed.

Before I proceed any further, here is the right place for a word of warning. If you are one of those ancient-minded people who believe something of the sort that God created man by cutting off a chunk of his divine thigh and subsequently came to favor that one particular group of humans you happen to be a member of, you may as well abandon this read right now. There is little chance you will understand anything. This discourse primarily addresses people who have an elementary understanding of how biological organisms came to exist via evolution by natural selection.

Before we get into human history, it will greatly simplify the argument to first look at the history of another species. We could use any animal or plant, so let us choose one at random.

The history of the American bison

If the above heading sounds a bit too tedious for a subject, do not worry. It is going to be very short.

Around 55 million years ago, a few million years after dinosaurs went extinct, a new family of plant species appeared and rapidly took over large portions of the Earth’s land surface. Known as the family of Poaceae amongst scientists, all of us are familiar with their common name: grass. A set of geographical circumstances led to the evolution of these plants, but since we do not here examine the history of grass, we do only care about the fact of its appearance.

Over a long period of random genetic mutations, a plethora of new animal species evolved specializing in consuming this new, abundant energy source, known collectively as Graminivores. Out of a long lineage of such creatures, some 5 to 10 million years ago, an organism evolved that was particularly adapted to consuming the grasses of the North American pastures. We now call it the American bison.

Innumerable generations of these animals lived nearly identical lives: aggregating in large herds, migrating from rain to rain, grazing all day long, and propagating to such population levels as the available grass sufficed to maintain. Then a new bipedal animal came about, hunted them to near extinction, and took over their historical grazing grounds to artificially breed other species of plants and animals, leaving only remnants of their populations surviving within so-proclaimed protection areas… The end.

I told you this is going to be a very short story. The reason I cite it is that it makes it plainly obvious to understand how the history of a biological organism is solely dependent on external, geographical and ecological, factors. I think that is straightforward for anyone to grasp. There was nothing bisons could do to alter the course of their history. Where grass is bison is until the factors change.

Humans also are biological organisms. And however much this may strike – or even offend – some, their history has followed much the same pattern as the one of any other organism, albeit in much more intricate ways which I will now discuss.

The history of human

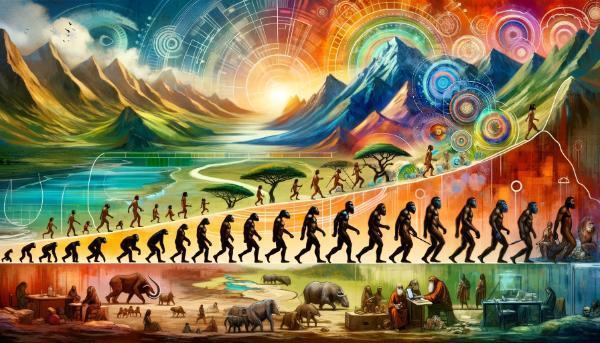

Some 4 million years ago, a most astounding genetic accident occurred in the East African savannah. Out of a primates group that already had abandoned their arboreal lifestyle, some one individual stood up on its hindlimbs and began to falter its way above the tall grasses. This would come to be the singularly most critical mutation that biological evolution on planet Earth has ever undergone; a mutation that would eventually give rise to a species that specialized in rapidly adapting to and surviving any geographical conditions, thus becoming the absolute master of the global ecosystem.

For one thing, bipedalism saved its adopters an enormous amount of energy that was previously expended for locomotion. Most importantly, early bipeds were left with two lame, useless forelimbs that over time evolved to the most sophisticated instrument of environment manipulation that biology has ever designed.

The human hand is the only biological device capable of handling the external world in specific and complex ways. It was the possession of this most invaluable tool that led early humanoids to gradually develop larger and more powerful brains. Why? Simply because they had an application for them.

Imagine a crazy scientist who somehow implants an intelligence a hundred times greater than a human’s into a dog’s head… What would be the first thing you’d set about doing if you were that canine genius? Probably you’d fancy some protection from the elements. You’d carry a number of sticks over to your preferred site with your mouth, and then you’d try to build them into a nice cozy doghouse… until you realize that you utterly lack the technical means to do so, give up, and get back to scratching.

Animals did not develop large brains because they have no use for them. An animal first needs to be able to draw a circle with its finger on the ground before it can conceive π. It needs to be able to cut wood and stone into geometrical shapes suitable to be combined into larger structures before coming up with the Pythagorean theorem. And only one animal has this ability. Only we have hands.

Humanoids needed a lot of processing power to visualize (imagine), select, and execute possible edits that they could bring about in reality out of an infinite range of applications their hands had empowered them with. Having developed minds that could formulate elaborate, abstract concepts, it was only natural to also develop the appropriate language to communicate these concepts with each other so as to undertake ever more demanding, shared endeavors.

Our species’ closest genetic relatives, apes, can form collectives of up to a maximum of 15 or 20 individuals. Put 40 orangutans together, and half of them are bound to be killed by the other half before long. This is so because their economies are physiologically limited to foraging leaves. A family of 15 can offer more effective protection against predators and facilitate better chances of reproduction, but a family of 40 would need a larger territory to feed than it makes economic sense to band together in the same place. Thus the size of an ape society is strictly confined by economic factors. After a certain population threshold, adding more individuals will only harm rather than benefit the collective welfare of the troop.

Humans, on the other hand, due to the potentially infinite applications of their collective hand- and brainpower, are via language capable of combining into ever-larger collectives, while ever augmenting the average wellbeing of each individual in the group. It starts like this: Alright, I can make spears, and together with my brothers we can hunt down an antelope. Why not ally with my cousins, too, and try to take down a mammoth…? And it leads to: Okey, let’s get together a couple of dozen of nations and construct and gigantic nuclear fusion reactor to experiment with creating a little sun on the surface of the Earth.

The entire history of humanity can thus be summarized into this simple sentence: Human history is the chronicle of progressive events that enabled humans to overcome geographic obstacles and integrate into evermore extensive and complex networks of collaboration.

This human history can be divided into three major phases, defined by the structure and range of their economies, as well as the ideological and political systems that these entailed. Be reminded that by economy is not implied money or finance, which are but a product, or utensil, of the economy. A human economy is plainly the collective amount of effort a society undertakes to, by order of imperativeness, secure its chances of survival, increase its comfort and pleasure, and enhance its understanding of objective reality – or its consciousness.

So let’s have a brief journey through these three historic stages of humanity, as well as the fourth one, whose impending emergence we can by now confidently predict. The titles I have given to these four eras of humanity are comprised by three words each, which respectively describe: first and foremost their economies, the ideological beliefs that linked together the societies that operated these economies (or you may say their religions), and the political structures that were needed to regulate and consolidate these economies.

Foraging, Animism, Tribalism

Homo Sapiens – that is we – evolved out of antecedent hominids in East Africa some 200 to 300 thousand years ago. To clarify, we know this because we possess actual human skeletons and tools that we found in the region and can determine their age via scientific dating methods of indisputable veracity; we do not speculate this because we found it in some superannuated fairytale that we were brainwashed since babies to believe was written by a too-anxious-about-humans god-creator of sorts.

But since this is a human history particularly knitted with geography, let us begin at a point when an alteration of the prevalent geographical conditions induced the first major event in our species’ history. Some 70,000 years ago, the most dramatic geological event humans ever experienced took place. On the island of Sumatra, a supervolcano known as Toba erupted in what so far remains the last supervolcanic eruption in Earth’s history.

Supervolcanoes get their prefix for a good reason. The sheer volume of energy they release is not even closely comparable to any volcanic eruption we have witnessed within the period of written history. The eruption in question is believed to have resulted in a volcanic winter of up to a full decade, and a millennium-long cooling episode thereafter. I will not go here into details about what these things are. What is important for us now is that they meant disaster for life and mass extinction. In the years following the eruption, most living things perished, and among them humans.

This event led to what is now referred to as the genetic bottleneck. Between a couple of thousand and a couple of ten thousand humans are estimated to have survived the Toba eruption, from whom I, you, and all modern humans descend. Searching for scarce food, those people migrated in every direction and gradually came to inhabit almost the entirety of the planet.

Over the generations, humans ended up segregated into countless, mostly isolated tribes that must have numbered between 100 and 200 individuals each. Those early humans already had the linguistic capacity and economic imperative to form much larger collectives than their arboreal relatives. It made perfect economic sense to maintain enough population to form large troops to send out hunting big prey, while others scoured for fruit and roots, and yet others stayed back in the cave tending to the fire, cooking, making tools and garments, and whatever else they were doing… but just enough for all that. Those early human societies could not grow larger than the availability of resources within a reasonable distance from the cave permitted.

Although tribes may have engaged in occasional bartering, distances between them were generally so great that intertribal contacts were rare and attitudes hostile. Every tribe developed its own unique language, religion, regime, and microculture.

Since their economies functioned much the same way, their religions and regimes, though different in details, shared the same fundamental characteristics.

Their religions were centered around the concept of the soul: some mysterious vitalizing force that must have permeated every thing, living or not. Since they hadn’t yet achieved any crucial advantage over the rest of the ecosystem and their surrounding geographic terrains (they were pretty much as likely to eat an animal as they were to be eaten by some other; they could drοwn in water as much as they could drink it), they hadn’t yet acquired any significant sense of self-importance. If anything, a large solid rock must have felt superior to them, as, unlike them, it was seemingly eternal, thus worthy to be worshipped.

Their tribal regimes, just like the ones of most other gregarious animals, must have been mostly constructed on the basis of muscle-power hierarchy. The strongest male would naturally dominate the rest of the tribe. But at the same time, as knowledge (or wisdom) was gaining importance for survival, the notion of elderism must have also arisen in these primitive societies, sometimes allowing older and weaker men to impose themselves over the younger and stronger ones.

Although human concentrations during that era naturally grew denser in the warmer and more bountiful regions of the Earth, no single tribe worldwide ever developed a notably superior culture. The lives of all tribesmen that lived throughout the tens of thousands of years the paleolithic age lasted would seem to us all but identical. All humans were as powerless before their geographical constraints.

But that was to change with the next major climatic event, when geography favored some humans way more than others.

Agriculture, Theism, Militarism

The last ice age ended about 10,000 years prior to the present day. Mean temperatures began to rise and glaciers to melt, allowing humans to further multiply and move into norther latitudes. The sea level soared, initiating the universal flood myths. Most important of all, big rivers began to flow.

Seven of these rivers flowed over lands suitable for intense human activity: unforested flat lands within the human organism’s ideal temperature range. These rivers were: the Nile in Egypt; the Tigris and Euphrates in Mesopotamia; the Indus and Ganges in India; and the Yangtze and Yellow River in China.

Unlike, say, the Congo, where the dense jungle could not allow broad human collectives to form, or the Mississippi, where humans had hardly yet even set foot, these seven rivers flowed through areas already teeming with stone-age people and featuring geographies optimal for further human expansion. Those people that happened to be there at that time were the lucky ones, as they went down in history as the founders of the first civilizations.

More or less simultaneously and independently from each other, numerous bands of roving hunters hit various spots along the banks of the seven rivers. What they saw there were huge herds of large animals flocking nonstop to the banks to drink water. Having a constant supply of both meat and water, it didn’t take much thought for them to quit wandering altogether and settle down. Thereafter, it didn’t take them long to figure out that they can fence and domesticate some of these animals, saving the effort of hunting. Nor did it take them long to work out a way to controlledly cultivate plants in the fertile mud the deflooding rivers left behind.

Agriculture resulted in a massive food surplus for its early adopters. The farming work of each individual human sufficed to feed a human several times over. Human populations expanded proportionately with the growth of food production. Rudimentary settlements spread into cities maintaining thousands of individuals, of whom only a fraction needed to be occupied with providing food for all of them. A profusion of new professions was invented to make the additional population worth the meal they did not directly work for. Building, woodcraft, metallurgy, warfighting, soothsaying… a cornucopia of new, specialized crafts emerged to facilitate the formation and functionality of ever-larger human collectives.

Animism could not do the trick anymore for binding such big societies together. Having taken control of animals and plants while remaining largely protected from wild animals and weather within their walls, humans had incontrovertibly positioned themselves above the rest of the ecosystem. New idealistic systems were developed to morally justify human dominance. These systems are known collectively as theistic religions. They all have in common the belief in some supreme, ethereal beings that created the world for a particular human group to reign in.

Since cities hosted much greater numbers of people than it would allow for kinship to be traceable between them, tribalism also was rendered irrelevant. Since potentially hundreds of equally strong or wise males could cohabit within them, strictly animalistic hierarchies became unsustainable methods for preserving order. Power wielding shifted from individual physical strength to politics; from whom had the biggest muscles to whom could employ the biggest cunningness and social intelligence to accumulate wealth and command the largest collective muscle. Power throughout the entirety of the agricultural era essentially belonged to whomever obtained the means to raise the strongest army; whether an individual, such as a king, an emperor, or a high priest; or an affiliation of individuals, such as an alliance of aristocrats, a council of elders, or a democratic assembly.

As the economic benefits of expertise became obvious, means like the wheel and navigation evolved into arts that allowed city-level specialization and interurban trade to flourish. Cities eventually combined into sophisticated trade networks that matured into vast kingdoms and empires spanning entire lengths of rivers and expanding rapidly away from their banks.

Trading quickly became the most lucrative occupation, merchants became the principal wealth-accumulators and hence army-raisers, and navigation and shipbuilding became the most valuable crafts. When the latter two crafts advanced sufficiently, civilization was bound to spread out like a virus across the seas. The obvious place for it to start expanding was the Mediterranean Sea.

Here I may have to disappoint some of my Greek compatriots. In contrary to what many of them believe, their ancestors did not develop a wonderful culture because anything was excelling about their physical and mental abilities, but simply because they happened to be situated in Greece.

As coasts across the western Mediterranean and Black seas began to – initially by the Phoenicians – get integrated into the old trading networks of the Middle East, Greece was located in the ideal position to control the maritime trade routes and become the new barycenter of Western civilization. (Western here is used in geographical rather than cultural terms, distinguishing from the second, still-isolated main epicenter of civilization east of the Himalayas.) Besides its evident strategic position, Greece was also endowed with a naturally fortified geography, which, although it disallowed them to link into broader political entities, granted the Greek cities the necessary safety needed to amass trade riches.

These Greek cities, via their commercial empires, managed to achieve an unprecedented level of prosperity. This in turn spawned an unparalleled excess of human capital: people who could now afford the luxury of lounging all-day-long under an olive tree, pondering stuff like stars, life, numbers, and beauty. A whole new set of occupations cropped up that essentially specialized in generating, organizing, storing, and transmitting information. That was the first time a human economy, though still only superficially and exceptionally, transcended geography, and ideas acquired value.

Later on, as civilization infiltrated the totality of the Mediterranean coasts, the commercial barycenter was pushed westward, and the sea became ridden off looting tribes and much safer to navigate, Greece lost its geopolitical prominence. Having less to worry about roaming pirates and barbaric hinterlanders, citizens could now safely settle low in new fertile plains and develop strong local economies in tandem with their commercial activities.

A city on the bank of the Tiber River in central Italy proved to be the ideal location to centralize the administration of this now-possible to exist trans-Mediterranean trading empire. Rome enjoyed plenty of local resources to maintain a huge population; it was decently protected by the long Italian peninsula and the hardly surmountable Alpic mountain range; it had easy access to both the western and eastern portions of the Mediterranean, while it was in close vicinity to the only navigable passage between the two, for which it vied with Carthage as the key to turning the Mediterranean into a private lake.

It was shortly before the peak of the Roman Empire the silk road opened, for the first time connecting the two theretofore partitioned civilization hubs west and east of the Himalayas. Both the Mediterranean and the Chinese hubs, as well as the Indian and Persian ones in between, benefitted greatly from this new intercontinental trade. All regions involved experienced their ancient pinnacle of glory and prosperity. But then disaster stroke.

Ironically, the very trading route that propelled civilization’s greatest advance was destined to trigger its downfall. Apart from treasured merchandise, merchants also brought back home new diseases, for which their countrypeople utterly lacked immunity. Populations in Asia, Africa, and Europe were decimated. Central Euroasian nomads, also afflicted by disease and famine, invaded and ransacked the suffering civilized lands. The capitals of the Romans and the Han, as well as all major cities worldwide, were deserted, depopulated. The Middle Ages had begun.

As humans perished and their economies backslid precipitously, idealistic and political institutions also were transformed. What started as a peripheral merge of a desert tribe’s monotheism with imported, pacifistic oriental ideals, evolved into a universally scoped, austere, obscurantist monotheism that best expressed its times of desperation and gradually replaced the previous, vibrant polytheistic religions.

Before civilization had any chance to stand on its feet again, catastrophe hit anew. This time it didn’t come from a new continent they began trading with, but from a continent they didn’t yet know existed. In 536 AD, a massive volcano erupted in Central America. It wasn’t anywhere nearly as powerful as the supervolcanic eruption of Toba, but still enough to cast at least a year of volcanic winter and long-term climatic disturbances. Crops failed, corpses piled, diseases spread, populations were exterminated.

Christianity further hardened, and a whole new, rival obscurantist religion sprouted. Their lands left utterly desertified after the eruption, hordes of starved warriors raged out of the Arabian Peninsula, conquered the Middle East and half the Mediterranean, and imposed on it their own rough version of Judaic monotheism. Aptly expressing the misery of their times, these religious organizations quickly became the leading army-raisers and de facto controllers of what was left of civilization.

But sure enough, civilization did gradually recover. Ships sailed once more in the rivers, and along the coasts of the Indian Ocean, the Mediterranean, and the Baltic. And they were just about to venture across the oceans, bringing about the second major economic paradigm shift in human history.

Industry, Humanism, Statism

The reason this article has been so lopsidedly focused on Western civilization is only that it’s written in a Western language, principally addressing a Western audience. The Chinese civilization developed along very similar lines, the main difference being that, since the very inception of civilization, China had always been a much richer and more advanced culture than Europe. In particular, China has historically been an average of three times wealthier due to it having been an average of three times more populous. And that has been so because of rice, which is thrice more effective than wheat or any other western staple crop, meaning that a hectare of rice can sustain three times more people than a hectare of wheat. In addition to this, China’s geography, particularly its plentifulness of natural waterways, allowed for the region’s thorougher integration.

China’s economic and cultural paramountcy was matched, and eventually superseded, by the West only after the latter managed to incorporate the New World into its commercial web, for the first time forming a larger economic collective than China. The reason why China, howbeit a more technologically and financially potent civilization it was, wasn’t first to discover and colonize America and other remote lands was again of a geographic nature. For one thing, the Pacific Ocean is much wider than the Atlantic; it’s hard to imagine humans becoming capable of sailing across the Pacific before the much narrower Atlantic. Reinforcing this, the second reason is that the Western civilization, evolving along irregular coastlines with many peninsulas, gulfs, and islands, enjoyed a much more favorable geography to develop the open-sea sailing tradition that would eventually yield the skill to traverse entire oceans.

Just like the core of Western civilization shifted from the Middle Eastern rivers and coasts to Greece and Italy as its range expanded westward during antiquity, it was only logical for it to move further west to lands that best accommodated the perpetration of the new transoceanic trade. The west European and east North American coasts, being climatically optimal for human labor and situated on either end of the Atlantic Ocean’s shortest stretch, were naturally the principal beneficiaries of this new, lucrative commercial activity. Being, in addition, a naturally defended island, Britain inevitably became the one country to reap the bulk of the trade’s profits, form the first truly global empire, and launch the second major transition of humanity: the Industrial Revolution.

We saw earlier how the human hand with its opposable thumb and the sophisticated brain that it necessitated was the singular biological development that individuated our species from all other creatures. This development entailed an economic imperative for humans to combine into larger and larger collectives and effectuate steadily more fundamental changes in their environmental reality. But as these collectives began approaching global dimensions, humanity’s biological means reached their limits.

Until the 19th century, all human endeavors were mostly restricted to the usage of either their own or their domesticated animals’ chemical energy (with only minimal employment of non-living energy sources such as fire and wind). The only way for humanity to undertake more consequential projects was to assimilate more biological muscle power, which allowed for only a linear increase in its collective capacity. When the whole of humanity had nearly fused into a single network of cooperation, novel means of exponential capacity enhancement needed to be invented if an evolutionary standstill was to be evaded.

The Industrial Revolution may ultimately be regarded as Evolution’s outsourcing trick. Engines may be regarded as external mitochondria; factories as external muscles and hands; trains as external legs; computers as external brains… all of them but artificial, inanimate extensions of Evolution’s sublimest biological apparatus.

Industry gave humanity a prodigious degree of control over the rest of the ecosystem and environment in its wholeness, which led to a relevant update of its religious and political institutions.

Traditional theism was not compatible anymore with the scientific revolution that was powering the new industrial economy. So it got gradually replaced by the notion of humanism. Humans were not any longer a divine creator’s favorite opus, obliged to submissively and helplessly suffer life in hope of a better afterlife. Now they could exert such influence over reality that they were able to make actual life better, thus elevating their self-regard and conceptually converting their very selves into divine creators.

Humanism may be regarded as our era’s universal religion, even though we don’t commonly define it as such. Sure, many individuals, even in the world’s most advanced contemporary societies, still today identify themselves as Christians, Muslims, or whatever other theists. But their practicing these obsolete religious traditions is but an inconsequential cultural habit; no less a persisting residue of theistic customs in the humanistic era than kissing pieces of wood was an animistic residue in the theistic era. You may attend ceremonies in some place of worship, even experiencing spiritual rapture when you do so, but unless you are a soldier of ISIS, an Amish, or whatever other kind of fundamentalist bigot, you aren’t going to resort to some collection of ancient myths to resolve a legal or moral issue. Instead, you will consult modern juristic and philosophical works based on universal human rights.

Several political entities spanning huge geographic areas were formed prior to the Industrial Revolution. But these were only loose associations of culturally diverse societies, whose main task was to maintain trading routes open for a minimal volume of commerce. But for industrialization to take place, a whole new model for a political unit had to be designed. This model became what we now call a nation-state.

For factories to operate and access markets; for advanced commerce to flourish; for order to be maintained among rapidly growing populations in monstrously big cities… a whole new set of elaborate infrastructure and complex bureaucracies had to be introduced. For such immense numbers of individuals to so intricately act conjunctively with each other, new standard languages and strong collective identities had to be invented. These were encompassed under the aegis of the notion of the nation.

Most of the early industrial states, like the European powers or Japan, constructed their national identities upon ethnic bases. The early US constructed it upon a racial basis. Others, like the modern US or the Soviet Union, fabricated national identities out of purely ideological backgrounds. Many of the countries still striving to develop in the 21st century, struggle so mostly for failing to forge a robust collective identity necessary to establish an efficient state.

On whatever foundations the national identities of modern states have been based on, they did not prevail easily. Whether via centrally-planned, universal education or violence, the faith in the nation was systematically imposed on the states’ subjects over a long and painstaking process. All the excruciating turmoil humanity underwent during the first half of the 20th century may ultimately be attributed to social friction produced during the final transition from agricultural to industrial economies and from communal to national identities. Now that we are on the threshold of another crucial transition, we must be extremely cautious and wise to avoid the repetition of a similar but magnified turmoil.

Data, Noism, Universalism

We are living in the age of advanced economic globalization. Consider for a moment the process that led to you possessing the device you are now reading this article in. Thousands of people have worked to extract all the different raw materials that comprise it from all over the world. Yet more thousands have worked to transport these materials to innumerable factories worldwide that manufactured all the different parts it consists of, while more have worked to design every piece of hardware and software that make up the final product, and yet more to ultimately deliver that to your local store or your door. All that while millions have worked to design and build every piece of machinery needed to manufacture and transport every component of the device, and more millions have worked to feed, house, and clothe the other millions while they’ve been busy with creating machines… You get the point. Nearly the entirety of humanity has collaborated for making it possible that you can obtain this device, or anything else for that matter, for the cost you did.

Globalization is here to stay. The economy does never backtrack if not forced to by external, inescapable factors. But ideological and political institutions have always been slow to catch up with the economy’s quick pace. That’s because, unlike the economy, which is versatile and evolves spontaneously, these institutions are rigid by design; eg, there wouldn’t be much use for a constitution if anyone could sit down and revise at any time. But sure enough, they do sluggishly change to conform with the pertinent economy they trail and are meant to assist.

Cavemen did put up resistance against civilians usurping their hunting grounds to build cities and plant farms, but they did eventually get either absorbed or obliterated. Free cities and communities refused to give up their peculiar autonomy, languages, and customs in favor of a national identity, but in the long run, they did get assimilated by the nation one way or another. It is precisely that other way’s avoidance that should be considered as the most urgent affair of our generation.

Nationalism and other antiquated ideological schemes are beefing up for their final struggle against Globalization, but their resistance isn’t going to be less futile than the one of the community against the nation, the one of the tribe against the city, or the one of wildlife against human. As we should be understanding, human is a part of nature, human history is but a product of geographic and other natural factors, and Globalization is no less inevitable than any natural phenomenon. We should consider ourselves very lucky for being, for the first time throughout this history, able to comprehend that the great ideas we fight for are but ephemeral fancies of our abstract minds, and perhaps, this time, skip fighting altogether and unanimously contribute to a smooth transition to our logical next phase, thus becoming ourselves a part of the future rather than a relic of the past.

Anyhow, whether smoothly or turbulently, we are about to be ushered into the next stage of human history, which, more precisely, is going to be the end of human history and the beginning of a radically novel mode of Evolution.

Evolution has so far acted upon the Earth’s matter via a random process of natural selection. Since self-replicating patterns of matter emerged, they entered into a fierce competition between them to – by means of the phenotypic effects they could enact in the environment – claim the available resources and the right to propagate. But a replicator’s success – whether a gene, an organism, or a culture – has forever been dependent on sheer chance.

It owed solely to the vastly long time parameter given that a random evolutionary algorithm managed to produce this astounding life complexity we witness around us. But now, finally, having passed that critical threshold of procreating a device adept to comprehend and hack the very algorithm that begot it, Evolution is ripe to move past the randomness of natural selection and advance further by employing a method of premeditated design.

The genetic science is progressing by leaps and bounds, and the day is foreseeable when we will be able to design our bodies and brains down to the last detail. Whether for utility or aesthetics, the range of possible forms we could decide to acquire will be limited only by physical laws. Hardly any of these new life forms – whether born a human or not – will have a good reason to even remotely resemble a human anymore. That day will be the last day for humanism.

If we are to thrive in that future, we are better to soon start unclinging from our humanistic tradition and embrace a new apposite dogma. Since our physiology will no longer be relevant as a common identifiable trait among us, we will need to start identifying ourselves as our sole remaining common characteristic: consciousness itself. In lack of an established term in my knowledge accurately describing this social-binding ideology of the future, I like to call it noism.

Earlier in this article, in order to more easily see how geography has dictated human history, we looked at the history of another, simpler animal. Now, in order to envision how the evolutionary history will proceed beyond humans and ultimately engulf geography itself, it may be useful to look at an even more antecedent stage of Evolution.

Cells, unicellular organisms, have lived on this planet independently for billions of years before humans, rats, lizards, fish, sponges, or any multicellular organisms came about. Innumerable of their generations went by before they, somehow, began to form collectives and develop action potentials to communicate between them, which eventually grew into full-fledged nervous systems that turned them into unitary organisms with centralized brains and individual self-perceptions.

Understanding this step of evolutionary history, one should ask: What laws of physics would prohibit such a process from repeating again on a much larger scale? Why should we regard human’s infinitesimally brief existence as the apex of Evolution? Why should we believe that we have any more free will than cells had to decide whether to integrate into more complex organisms or not? What would prevent the Internet from evolving into a full-fledged, global nervous system and the Earth from turning into a single conscious mind with its own peculiar self-perception, ego, will, and existential anxiety?