Mosul has never been your typical travel bucket-list inclusion. More recently, it may have rather topped the list of your most sure-to-get-killed places on the planet—by murder, or suicide if by any chance you are a jihadi. But since it got liberated from ISIS in July 2017, it’s been twinkling on my wanderlust’s radar.

I intend this as a unique travel story and not a rephrasing of half the Wikipedia’s entry. But for everyone to follow a bit more easily, here’s a summation of the historical background in one brief paragraph:

Amid the anarchy bred in Syria since the onset of the civil war in 2011, hordes of international Islamic lunatics flocked into the country, gained control of large swathes of defenseless land, and crossed into Iraq, where they captured Mosul: a vibrant, 4,500-year-old city of 1.6 million inhabitants. They imposed on it sharia, looted and vandalized, executed thousands and displaced half a million, and terrorized for three years until, after nine months of baneful fighting, an international coalition of forces liberated the city.

I don’t know if you attended the events at all, but they were absolutely shocking and soul-shuddering; pure madness, like all the globe’s loony bins had broken open and their runaway inmates teamed up to enforce the rule of lunacy onto the sane population.

Bearded sociopaths roamed around like black-robed Smurfs, waving belligerent flags and brandishing Kalashnikovs. They blew up cultural heritage treasures, stoned women in public squares, raped and slaughtered, live-streamed decapitations of journalists… all in the name of God and in the hope of being granted a couple of extra virgins upon their glorified admission in Heaven. The whole thing felt kinda like watching GTA being played out in the real world.

I was curious to see with my own eyes how the city recovers after this most surreal calamity. My opportunity to visit it presented itself in October 2021.

This story is an excerpt from my book "Backpacking Iraq", wherein I recount my journey through this misunderstood and fascinating country. The entire book is available to read online for free. But if you'd like to get it on your e-reader or as physical copy (and, doing so, support my creative activity), you may check it out on Amazon.

We were in neighboring Iraqi Kurdistan’s capital, Erbil, and were keen to work out a way to undertake the mere two-hour drive to Mosul. We first got in touch with a couple of fixers (professionals specializing in bringing journalists or any adventure enthusiasts to danger-prone war zones). But we soon found out that, by 2021, this trip was rather straightforward to do alone and unaided. The sole requirement was to obtain a visa for the Republic of Iraq.

Since we had omitted to do that in advance at one of the country’s diplomatic missions, our only option was to fly to Baghdad and get the visa upon arrival at the airport. That’s what we did, and after allotting three days to explore Iraq’s capital city, we were ready to head back north towards the Nineveh Governorate.

Bright early morning, we got into a cab and requested to be driven to that one of Baghdad’s many terminals whence we’d been told we’d be able to catch a bus to Mosul. The driver dropped us off at the station’s entrance. An assembly of other drivers swarmed to us, raising an unintelligible Arabic babble, and attempted to have us boarded in one of their vehicles. Their fares were pretty fair for a comfortable, private ride. But besides saving money, we desired to travel authentically, mingling with the locals.

Assisted by the only man present who understood a little English, we explained ourselves and were led to a minivan about to depart for our destination.

In a gesture of hospitality, the chauffeur offered us the two comfier seats in the front. But another dude, possibly his boss, intervened and instead had us seated in the car’s crammed rear corner. If his reason was the one I thought about by myself, that was a great idea. With our two foreign faces on display right behind the windshield, they would stop and delay us at every military checkpoint, and we wouldn’t complete the journey even by tomorrow.

Hidden between the heads of the other passengers in the front, the curtain on the side, and the luggage pile in the back, we passed unnoticed and were casually beckoned to proceed with a wigwagging hand by each controlling soldier along the way. So, having made but one stop for lunch at a rudimentary service station, we quickly covered the 400 km of endless straight road across the Mesopotamian desert. And by late afternoon, we turned up at the final checkpoint before Mosul’s outskirts.

This guy was diligent. He squinted through the windows, scanned all faces, and paused at ours confounded… Our co-passengers were growing impatient in the while it took him to go through consecutive calls discussing our passports with his superiors. Everyone was relieved when he ultimately returned them and let us go.

And then, down the plain beyond the next purview, appeared the once-gem of a city embracing the gently flowing blue waters of the Tigris River. The streets were deserted, and we before long arrived in the desolate bus station; no crowds of travelers, no busy bus companies’ staff, no touting vendors, no soul was present.

After the other passengers dispersed, only the two of us, together with the driver and another random dude, remained in the broad, vacant parking lot, overlooked by broken windows of uninhabited apartments. The driver treated us to a cup of tea while we waited for that taxi he called for us. We sat on the curb, trying to chat and taking selfies, until it came.

We drove along many wide, bare streets through various ruined neighborhoods. The best-preserved buildings had only a few bullet marks, shuttered windows, and maybe a chunk of mortar missing here and there. The worst ones were heaps of rubble. It is an uncommon experience to drive in a city of such a size with no traffic. It didn’t take long to cross the river and get off in front of our hotel.

We had a bit of daylight left and nothing much to carry. So we postponed our check-in to go for a little sunset stroll on an initial exploration of our new environs.

It so happened we were right beside the Grand Mosque of Mosul: an incomplete yet impressive architectural feat whose construction began during Saddam Hussein’s reign. A couple of workers stood by one entrance to the temple’s premises. I asked one whether we could enter, to which he replied with a facial expression that could be translated as “but of course not, you fool”. But that mattered little, as we could still walk freely around the one-foot-tall ledge that encircled the site and enjoy the splendid, golden-hour views of this imposing marvel of human existential vanity.

We photographed the monument from various appealing angles. But upon turning the corner to its river-facing side, a soldier scurried to us, shouting. He requested us to not take pictures, putting effort to appear strict, whereas in reality our presence amused him. We complied and strode into the backstreets.

This district was much better preserved than the other side of the river. Most buildings were intact, and many were inhabited. Bands of children gathered by the gates, watching us curiously and timidly. Adults noticed us as eagerly and swung friendly hands from further inside the yards.

Shortly before sunset, we stepped into our hotel’s reception. Although the staff spoke decent English, they couldn’t understand that we wanted the cheapest room; the one they had offered when we talked on the telephone yesterday. They made it a mission to force us to take either two separate bedrooms or—they didn’t care about a marriage certificate—the bloody suite.

“That’s not good for you,” they’d say every time I reiterated that what’s in fact good for us is the ground-floor bedroom with the shared bathroom. It took many repetitions until I convinced them.

Our windowless room contained nothing but four squeezed beds and bedside tables, a kettle with a half-foot power cable, and a single socket high on the wall. Outside, we had a coffee vending machine and a flight of steps to sit on in the tiny yard. Overall, it was a cute place to sleep for two nights. Besides, we wouldn’t spend much time inside.

Using myself as a table to boil water, I had a quick cup of tea, and when it got dark for good, we went out for dinner. My first impression of the city hadn’t left me too excited about what’s left of its culinary choice. But we were near its most lively street. It ran alongside an extensive prehistoric site. Street lights were sparse, but at least present. Its one side teemed with modern restaurants and teahouses. Many progressive companies and families socialized at their tables.

In the end, we opted in for a pizza. The cheese was melty and the crust yeasty and—no, joking; it was a nice pizza. We topped it off with a delicious waffle in a lovely lawned garden of a place and went to bed.

Then dawned our sole full day in Mosul; the one we had to take thorough advantage of. After a caffeine-and-nicotine dose, carrying but cameras and a small bag, we were out walking.

We headed straight towards the closest bridge over the Tigris and the old town that lay on the other side. The way thither ran through a rural stretch of land and along a narrow tributary channel. A herd of buffaloes raced down a sandy slope to the strand for a morning drink. It was a pleasant stroll in the soft matinal sunshine.

The bridge was relatively busy with vehicles and pedestrians. Sporadic minarets stuck out into the blue sky from the vast expanse of debris on the opposite side. The scene was heartbreaking; reminiscent of a WW2 documentary. The great river flowed at its ever-indifferent pace underneath. It moved me to contemplate how remarkably unaltered it must have remained throughout the millennia-long performance of human history’s drama on its banks.

The army stopped us no sooner than we stepped off the bridge. They were baffled to see us alone and on foot—whatever foreign visitors they see are commonly accompanied by guides with cars. They must have thought we were lost or something. As soon as they realized that we know what we are doing, they let us go with cordial smiles.

This was the only time we got controlled until late in the afternoon. Unlike in Baghdad, where they stopped us at every second crossroad, here we didn’t notice a significant military presence. This justified to my eyes the complaint we heard from many locals: that the central government abandons them now again, just like they did back then.

And we found ourselves roaming around the once-magnificent, now-ruined Old City of Mosul. Most buildings were uninhabitable, and the ones that weren’t technically so were inhabited only by compromise. It saddened me I didn’t observe any single serious restoration project being underway. The most I saw were individual citizens struggling with bare manpower and hand tools to improve however they could their dilapidated properties.

The people were at least as friendly and noble-mannered as in Baghdad, the difference here being that they were much fewer. Everyone greeted us mirthfully upon our passage and uttered kind-sounding words, which I couldn’t, unfortunately, comprehend. Many posed proudly for pictures. Others pulled out their mobiles and bustled around us for barrages of selfies.

Our steps led us past the Great Mosque of al-Nuri: a world-heritage monument that stood for eight whole centuries until the archi-madman by the name of al-Baghdadi ordered its demolition after giving there his last and first, maniacal live speech. Despite a UNESCO noticeboard informing about its purported renovation, there wasn’t a single worker on site.

A small teashop operated across the street from the mosque, with a sole outdoor table beside a jumble of detritus. We sat there for a break together with the owner and a bunch of his friends, who invited us for a cup of tea. They knew a few English words, and we got by with a somewhat interpretable chat.

It was getting hot, and the best continuation for our walk was in the narrow, shaded bystreets: a maze of twisting pathways with carved runnels on their concrete floors for sewage. It felt lonely in there. People already weren’t quite crowding in the main roads; off them, they were scarce.

One of the first humans we came across happened to know a fair much of English. We were checking out a cute little grassy patch on a fenced lot among the tight, ramshackle houses. A young man then materialized out of a parked car and walked to us, joyfully, patently proud of our interest in his creation. He explained that that was where his house used to stand; now, with care, he had turned it into the pretty lawn we were seeing. He invited us to his friend’s garden around the corner.

That fellow was bliss personified. As soon as we went past the narrow, arched stone gate, he jumped up and, exuding hilarity and contentment, exhibited the wonders of his sanguine creativity.

He maintained a literal little oasis amid the enveloping devastation. He grew various sorts of trees and exotic plants in and out of his impromptu greenhouse. The space was further decorated by clay jars and other artifacts of his own making. And all around and above, only tarnished walls to be seen.

A grandad with his grandson stopped by; then a group of students… Apparently, people from all over the city visited to enjoy the tranquility. The man had created all by himself what the municipality or the government had neglected to: a public park.

Our new friends then volunteered to give us a tour around the neighborhood. But as we stepped into the street, the next-door neighbors dragged us into their house, where a wedding was ongoing.

Colorful balloons, flowers, garlands, and string lights adorned the tiny, dim living room. Guests spanning the entire age range danced convivially to the traditional tunes a loudspeaker blared from one corner. In another corner, a man was preparing a big roll of kebab meat. A bedecked couch stood on the room’s most conspicuous post; a sort of throne for the newlywed couple.

The groom stood out instantly by his dapper attire, well-trimmed mustache, and cool sunglasses. The bride… I wasn’t sure whether she was present at all. I think they pointed to that mature veiled woman I took for the mother-in-law, but I didn’t want to insist on clarification in fear of insulting.

Everyone seemed excited about the surprising addition of us two on the guest list, pulling us to the dance floor and clicking consecutive selfies… everyone but the elderly woman who must have been the matriarch…

She looked displeased and anxious to throw us out; shunned the lens and strove with admonitions to bring her descendants to their right minds. Perhaps she felt a comedy was made of the serious affair of her blood’s perpetuation. She must have had enough when she raised a fuss and forced her progeny to kick us out politely. We wished a lifetime full of happiness and love and departed.

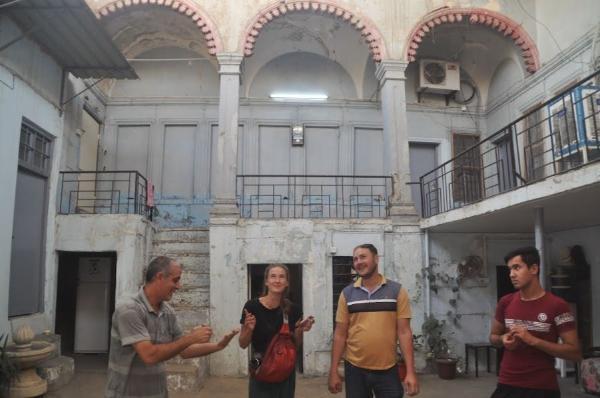

Our friends then showed us to a nearby 18th-century manor house. It featured an interior yard with a perimetric balcony and elaborate arches. Although faded, the walls were painted in the city’s characteristic electric blue color. A little stone fountain and various pretty, vintage items lay around. Despite being unoccupied, the house was in decent condition overall. It was the garden guy’s historic family house, which—maybe for lack of heirs—he alone used now as a warehouse and workshop.

We thanked our hosts for this excellent excursion and resumed our lone walk towards other neighborhoods… We went through several torn-down ones of them, warmed our hearts up by receiving the welcomeness of many heroic locals, and then we encountered that one human being who left me with the day’s most emotional memory…

In a broad, dusty, forsaken street, amid mounds of rubble and lost human possessions, stood a surviving building structure. Its pillars and beams were in place, but its several floors and walls were mostly missing. From the mishmash of construction-material bits that were scattered over the ground floor, a rueful tune diffused out to the street. Curiosity attracted us to its source.

It was produced by a young man. He stood still and alone atop the debris, moving but his vocal cords to weepingly sing what sounded like a kind of elegy. He looked completely removed from reality; didn’t budge an inch in reaction to our arrival. I doubted whether he’d noticed our presence at all right in front of his eyes. He only kept crooning lamenting words whose meaning’s guess alone pierced my heart.

The sun had begun its descent, and lunch was long overdue. Gastronomy in an Arabic city normally is an appropriate occasion for experiencing the paradox of choice, but here it made for the perfect example of scarcity. There weren’t more than a handful of semi-functional places serving food in the entire old town. After a quick meal in one of them, we retraced our steps towards the bridge we’d crossed in the morning.

Instead of heading back the same way, we took advantage of the remaining daylight to extend our exploratory walk around and past the next bridge.

We went through a roofed bazaar street. In previous, peaceful times, it must have been awash with folks. And still now, it was some levels up from deserted. Fresh fish and other comestibles were for sale at a few scattered stalls. Groups of old men puttered in a couple of small teahouses.

One of those companies invited us for a cup of tea. The lads who served us rejoiced in our—and especially my girlfriend’s—presence. Women—let alone blond, unveiled ones—do not make a common part of an Arabic teashop’s clientele. Poor Sophie, she got offended when they half-jokingly asked her to wash the dishes for them.

Leaving the bazaar, we found ourselves in another ravaged neighborhood. We got attracted to an unusually large accumulation of people in front of a wrecked edifice. It turned out to be a movie production crew from Kurdistan, working on some kind of war film. They were shooting a scene on that building’s roof and invited us upstairs to have a look.

Treading like those Korean guys in The Squid Games’ penultimate challenge, we cautiously climbed the three-or-so stories of crumbling stairs to the top. Crew members were busy with their equipment. Two boys stood by the rim and feigned a brawl for the camera, while a veiled old woman crouched beside them apathetically. The soft-lit view of the Tigris and the vast surrounding devastation was spectacular and poignant at the same time.

Back downstairs, we resumed our jaunt northward along the western bank of the river. This district was by far the worst-hit we saw in the entire city; utterly flattened. Only a few erect wall remnants jutted out from the immense succession of rubble heaps. A medley of personal articles littered the sea of broken building fragments, such as shreds of clothing, shoes, military paraphernalia, toys, and human bones.

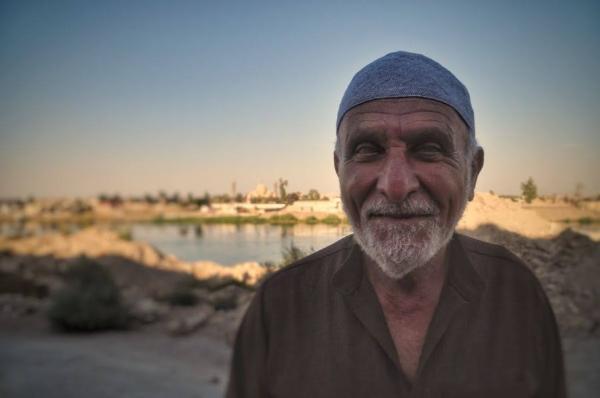

The locality must have once teemed with life, but now was totally devoid of it. The only human we crossed paths with was the best English speaker we met during our sojourn in the city…

An old man in a traditional Arab outfit spotted us from the distance and loped towards our part. He was a retired teacher who proved thrilled to see us and put his language skills to use. While giving us a tour of the area, he verbalized more eloquently than anyone else the collective lamentations and accusations of his co-citizens about their city’s tragic fate. He concluded with an absurd conspiracy theory alleging that the disaster was deliberately masterminded by an evil entente of the West, Israel, and Iran!

He eventually left us to go his way, and we continued on our own through the destroyed neighborhood. There was a crucial obstacle to the rebuilding efforts: the completion of an essential but formidable, preparatory task: the city’s demining. In a characteristic display of their petty, vile, squalid, cowardly inner selves… before sneaking away, blowing themselves up, or whatever else they may have done… the holy warriors ensured they’ll be remembered for long by trapping the whole ruined city with explosives, often hidden inside teddies and stuff.

Still to this day, fatal explosion accidents occur. It wasn’t a good idea to wander off the road and onto the rubble, but I hadn’t urinated all day; it was that or my trousers. Watching each of my steps, I advanced over the wreckage and clambered down into an explosion crater where I could relieve myself secluded from common view—I reasoned that, since something had already blasted in there, there was little chance of anything else being left unblasted.

Then I heard Sophie’s voice replying to the one of an unknown man out there. As I reappeared over the brim of the sinkhole, I saw a patrolling soldier looking for me. He thought I was taking pictures and was nice about it; only warned me about the danger I was already aware of and asked me to not step off the roads again. I wouldn’t have in the first place if it wasn’t so pressing.

Somewhat lighter, we left the riverbank and made our way to a better preserved, populated district. The first people we bumped into were three soldiers manning a checkpoint.

They detained us, took our passports, brought two stools, and let us wait on the roadside. At first, I thought they kept us only to kill their boredom, as was often the case. But it turned out they must have also assumed, like the previous ones, that we were lost and needed help. After half an hour of inaction, an English-speaking passerby interpreted that we were just heading to the bridge, intending to cross over to our hotel. Although still startled by our boldness, they let us carry on.

The bridge wasn’t of the pedestrian-friendly sort. Not that I expected it to have walking lanes and coin telescopes, but I hoped there would at least be a stairway to shortcut the 2-km extra way around the closest car junction. And indeed, there was such a thing, even though not quite what I imagined. We had to use a shaky wooden ladder to climb the first five-six vertical meters of the abutment’s stone base, and then crawl up a steep gravel slope, but we made it to the deck just fine.

The traffic was rather steady, though much short of what the bridge’s width suggested it was designed to accommodate. The deck was broken, probably shelled, in two different locations. They had installed portable military overpasses to patch the gaps. These were just wide enough to squeeze ourselves and brush past the passing cars’ mirrors, the while reciprocating the incredulously staring drivers’ greetings. A small construction crew working on some more permanent solution was the only one of its kind I saw around the city.

On the other side, a booming reverberation muffled the intermittent drone of the engines. It came from an array of bulky loudspeakers outside a venue of sorts below the bridge. A big festivity was taking place. It may have been a wedding; if so, markedly richer than the one we witnessed earlier.

Perhaps a hundred older men, dressed in their official thawbs, sat around a stage, where younger men performed ecstatic group dances, while little boys ran and played wildly all around. If you wonder where the gender counterpart was, I wonder too. The elderly smiled modestly in their seats; the lads cheered and gesticulated us to come down. I would love to have a closer look at the event, but that would mean either walking a long way around or jumping some fifteen meters down the bridge (no ladder here).

We continued onward, past the clamor, and began descending one of the bridge’s long, curved ramps. The traffic there was scant, only fitfully interrupting the ambient serenity. The sun was setting over the ruined city’s jagged western skyline and cast the warmest hues over the ground’s prevailing sandy tan. Together with this day, our experiences in Mosul were coming to an end.

It was dusk when we made it back to the hotel, where we met an American traveler and his guide with whom we first got acquainted a few days ago in Baghdad. We had dinner and went to bed early. At dawn, we departed all together back for Kurdistan, bidding farewell to this tormented but inspiring city, which, like a burnt forest, is bound to over time regenerate itself, fertilized by the ever-revitalizing force of human hope.

Photo Gallery

View (and if you want use) all my photographs from Mosul.