People often ask me how my relationships are with other humans while I travel all the time; whether I experience any emotional deprivation, being compelled to only develop strictly superficial ties, since limited time does not allow for a connection to deepen.

My answer to such questions is what I have understood. To wit, that they fool themselves terribly if they believe that the emotional depth of human contact depends on time; that they do not comprehend the nature of emotion, nor the one of time. Often, a brief interaction, the exchange of a few words, or even the fleeting intersection of two glances are over-sufficient to tighten an inextricable bond between two people.

Such was the case with that rare human being I was destined to meet that morning. We only hung out together for a few hours. I’m never going to see him again in my life, nor will I ever hear anything from him. But no doubt, the remembrance of him and the feelings he awakened in me will never fade until the last of my days.

All of us, I believe, are perpetually swinging back and forth on an emotional scale, at whose two extremes lay misanthropy and altruism. Getting acquainted with some of these people alone can give you a good push towards the latter.

So was I then ambling down Dar Es Salaam’s Morogoro Road towards the harbor when I suddenly took notice of that lad walking by my side. He began telling me stuff to which I initially paid no attention because I formed a biased presumption of him being a tout of the ferry companies. That impression of mine got soon dissolved, though; firstly by remarking his sophisticated English speech, and then by noting on his physiognomy that he wasn’t a local but came from the Horn of Africa instead.

I then halted for a moment to examine him. He was a young, shabby, emaciated chap. From whatever angle you looked at him, his whole appearance evinced dire hardships and affliction.

I got a bit puzzled over this, as I wasn’t used to seeing people in such extremely miserable conditions in that city, where the standard of living was generally decent for the African average. I observed his two tiny eyes lying deeply, like in two small caves, inside his fleshless eye sockets. A vague, bizarre glow that they emitted, transmitting some kind of superhuman serenity, was what motivated my curiosity to listen to his story. After I bought my ticket at the port, I invited him for a meal at a nearby canteen. While we sat there, he slowly recounted his life.

His name was Marty. He was 27 years old. He came from a village of Tigray in northern Ethiopia, where his father used to maintain a coffee plantation. There he lived a happy, peaceful, and well-off life with his family until, one morning, they got attacked by a group of Somali guerrillas who had crossed the border on a looting raid.

They plundered and set ablaze the entire property of his family. By and by, they tortured and slaughtered his parents and his fourteen siblings. As for him, they chopped off three of his one hand’s fingers with a machete and planted three bullets in his abdomen when, at some point, he took to his heels to save himself.

After all, he didn’t only manage to flee but to survive his injuries as well. Having gone through many adventures, he made it to a refugee camp in Kenya, where he gave himself up and remained a prisoner for three and a half years. And I say a prisoner because they, too, refugee camps, operate on precisely the same principles as all prisons worldwide: They receive funds by the state (the UN in this case) per capita. Hence they do their best to increase the numbers of convicts and consequently their revenues. Goodwillers to embezzle their shares will always emerge; it goes without saying.

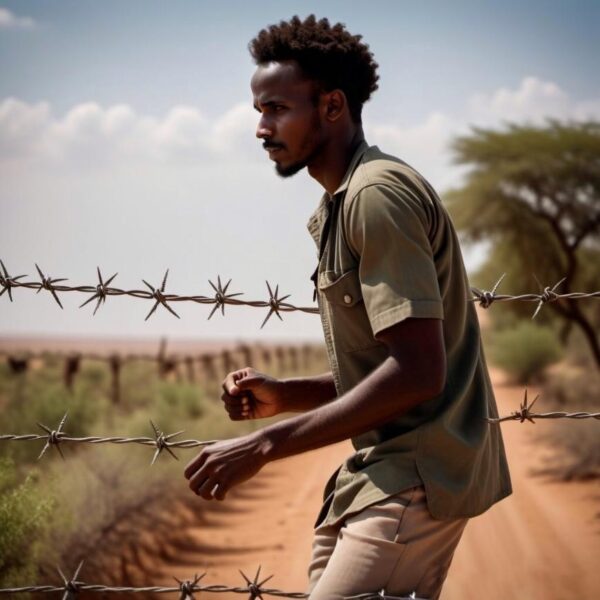

There, in the refugee prison, Marty learned to speak English. Eventually, when he understood for good that to be released was impossible, he escaped by jumping over the fence, slashing his arms severely on the barbed wire.

Thereafter, he made his way to Dar Es Salaam, hoping that he’ll manage to settle down and start a new life. Things did not turn out as ideal as he had imagined them, however. He had been there for a year already, living in the streets and running the constant risk of being arrested and imprisoned for having no papers – since, in our modern world, someone who does not carry an identification document is not considered someone, but rather no-one.

For all that time of his stay in the big city, he invariably ate thrice a week: on Sunday, on Tuesday, and on Friday when the church, the mandir, and the mosque respectively held their charity handouts. To the mosque, he went every day, as the wudu fountain was his sole reliable water source. On top of all the rest, he also had to fight against diabetes and arthritis, diseases which he had developed.

I’ve heard a lot, I’ve seen a lot, and I’ve learned how to remain dispassionate. Listening to and looking at that guy, however, I confess that my blood seethed, and I outright freaked out.

But Marty’s singularity did not inhere as much in his story itself as in his attitude towards it and life in general. While we were together, I was striving within me to understand: What could it be that gave him such strength to fight? What could it be that gave him the drive to constantly smile and laugh heartily at the slightest thing he deemed funny? What could it be that made him want to continue to live? Indeed, I never remember having met a more cheerful, smiling, and positive person.

After all, though, I think I figured it out. It was the ability to dream; to dream of something pure, noble, and high. I realized this when he spoke to me about his future plan, his dream. He yearned to return home. Deeply touched, I listened to him talking long about his birthplace while something like a divine thrill was flashing in his eyes.

We stayed together until the afternoon, nonstop discussing various intriguing topics: politics, history, society, man, soul, God… How wiser I felt after that association is beyond description.

In the end, I bid him farewell at the bus station. I had just bought him a ticket to the Kenyan border. There he would have to cross back clandestinely and… figure out what to do. A long journey back home was just beginning for Marty. I wished him good luck.

The story you've just read is a part of my "Real Stories of Real People" collection, wherein I narrate my encounters with various remarkable characters I've run into while traveling around the world. The entire collection is published on my blog and may be read here. But if you'd like to get them with you to the beach in your ebook reader or as a physical book, and very appreciatedly support my creative activity, go ahead and grab your copy from Amazon for the cost of a cup of coffee.