The quiet was absolute before it got interrupted by my ringing phone. Its screen was the sole radiant object within our otherwise pitch-dark room. I pressed the answer button to silence it and hear Ibraheem’s voice. “We are downstairs,” it said. “We’ll be there in a minute,” I responded. He was meant to come at 6 am, but it wasn’t even a quarter-to yet. I wiped the sleep off my eyes, nudged Sophie awake, and turned on the light.

Ibraheem was one of those professionals whose services I’ve hired on so rare occasions in my life: a tour guide. He had contacted us of his own accord after we posted a question on an Iraq-travel-related Facebook group a few days prior to our arrival in Baghdad. Under common circumstances, I would have ignored his reaching out. But a combination of factors led to us accepting his bid and planning a day trip together.

To begin with, we had very little time—three days in Baghdad—to organize an independent excursion out of the city (it’s not as if the Internet abounds with blogs on DIY travel around Iraq as it does for, say, Thailand or France). That the average Iraqi person speaks as much English as we do Arabic—that is zero—further complicated the task. That’s why we received Ibraheem’s previous day’s message as a boon.

He’d said he had a tour arranged with another guy for tomorrow. They’d be heading to Ancient Babylon—the exact place we were most eager to see—and we were welcome to join for a special price; only slightly higher than it’d cost us to get there by public transport. And they would also visit the site of Ezekiel’s Tomb…. We didn’t have to give it much thought.

Our hotel’s lounge was unlit and the reception desk vacant. I reflected with a tinge of disappointment on the paid-for breakfast we were going to miss. The dodgy street outside was murky and deserted. The guard was dozing in his shabby chair by the entrance, shotgun dangling from his shoulder. He didn’t notice our departure. A sole car lay parked across the road with its hazard lights on.

Ibraheem’s client turned out to be an American guy we’d seen at the airport last morning. He was waiting for his visa together with us. He introduced himself as Ty for Tyler. We greeted them both and took our seats in the car’s rear.

Not a trace of sunlight had yet infused the sky above the Iraqi capital. The megapolis’s notorious traffic hadn’t kicked in, and we rolled through its broad streets fast. We were soon on the motorway, speeding south and relishing the advent of dawn over the Mesopotamian plains.

To my satisfaction, Ty proved no less of a caffeine junkie than myself. So I didn’t have to be that dork who one-sidedly slows the group down at all costs. We jointly prompted Ibraheem to stop somewhere for a coffee in urgency.

There was that lad at a roadside stall who made for us two small yet strong cups of Nescafe. I still had to be the dork who alone stank the car up for ingesting my imperative dose of nicotine, too, but the guys seemed okay with that.

And we proceeded ahead, the cool morning breeze pouring in through the open windows, enjoying an alluring sunrise over the flat desert horizon and getting better acquainted with each other.

Tyler was a classic example of the 21st-century personal-freedom rebel. He had quit a lucrative job in the US tech sector to invest his savings and lead a life of world-traveling and self-development. Ibraheem, although he liked to boast about his gun collection, was the gentle-giant type—huge build, benign character; couldn’t imagine him hurting a fly. He was very young but smart and self-disciplined, focused on working his way up to riches.

Chat and all, time flew until we reached our destination.

This story is an excerpt from my book "Backpacking Iraq", wherein I recount my journey through this misunderstood and fascinating country. The entire book is available to read online for free. But if you'd like to get it on your e-reader or as physical copy (and, doing so, support my creative activity), you may check it out on Amazon.

Contrary to the norm at archeological sites of such acclaim, the parking lot before Babylon was all but empty. Whatever few cars were present belonged to workers. We didn’t see a single tourist.

There wasn’t anything like an office, or even a booth, by the entrance, but a couple of employees idled under a tree. They seemed gladdened by our arrival—presumably for both the profiting and boredom-killing prospects.

One of them, a puny man in his sixties, was to be our guide through the site; funny chap, combining a military-style mustache with a baseball cap. He claimed he’s been doing the job for his whole life, following his dad and granddad, who did it before him—very believable, given the well-practiced, tip-asking performance he put forth throughout the tour. He was also quite open about expressing his nostalgia for Saddam’s times—not surprising, since he was a member of one of those families who’d secured intergenerational government jobs.

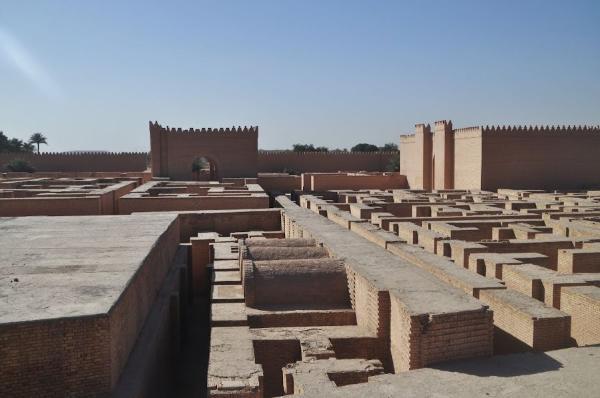

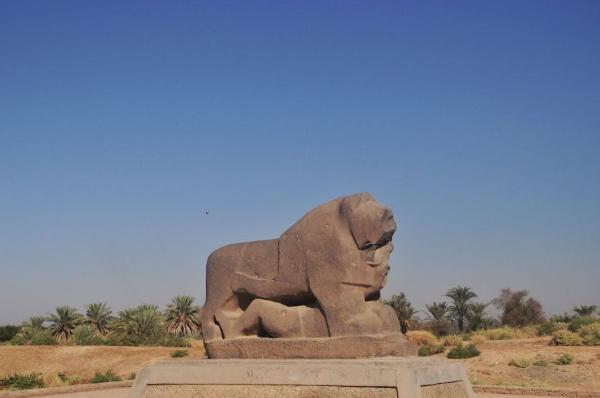

We paid the entry fee, received a brochure, and walked past the magnificent, deep-blue Gate of Ishtar onto the grounds of one of history’s most glorious cities. This gate, just like the entire complex, was, of course, a reconstruction, built atop the scant ancient ruins that were excavated from the 19th century onwards. Just a few street slabs and wall foundations of original structures were visible here and there.

The restoration project was initiated in 1978 by Saddam Hussein and was principally intended to gratify his own megalomania. Prior to his downfall, the site abounded with portraits, statues, and pompous inscriptions lionizing his overinflated ego. Imagine the sense of vainglory he must have experienced while staring at his creation from atop his nearby palace, comparing himself to grand Babylonian kings.

Anyhow, the compound constitutes quite a representative replica of the Neo-Babylonian Empire’s capital city. It was a moving experience to walk around this venerable site and visualize the daily life of its proto-civilized inhabitants.

Past the gate, we found ourselves in a plaza surrounded by tall, crenelated walls. An iron gate blocked access to the inner premises. The guide, in a sort of conspiratorial manner, unpocketed a big antique key and unlocked it. He alleged that this wasn’t included in the custom tour and made it appear as a special favor to us. But of course, it was a standard part of his soliciting performance.

Throughout the rest of the excursion, everything we did was to our exclusive privilege. It wasn’t allowed to go to certain places, take certain photographs, or touch certain objects… yet, assuming the risk himself, he let us do it all—because he liked us so much.

So signally fond he was of our persons that he gifted us some Chinese souvenir trinkets dubbed semi-precious stones. We tried to reject them with due politeness—as we weren’t intent on compensating him and had limited space to carry useless stuff—but he was too persistent. We later passed them on to some begging kids who looked much happier about their possession.

The tour soon ended back at the gate and the guide’s play culminated with a request for a tip. He pulled a face at our refusal, but what to do… I never liked the tipping culture, especially when I’m treated like an idiot instead of receiving decent service.

All the while, we could see Saddam’s stately palace imposed over the flat landscape from the top of a neighboring artificial hill. And that’s where we drove to thereafter.

A monumental structure, worthy of its owner’s vanity, it is but one of countless similar palaces he ordered built around the country. He rumoredly visited it only once before the Americans occupied it and turned it into a command center. It’s been left abandoned ever since their withdrawal in 2011.

A lone guard fooled around by the main entrance, embodying the state’s minimal effort to prevent the edifice from falling into further disarray. He seemed more interested in his mobile than in our arrival.

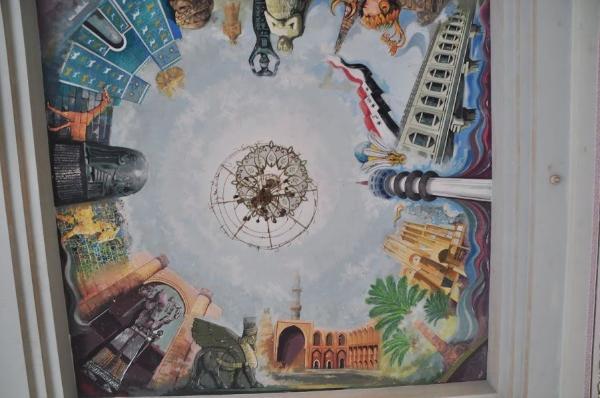

Despite all the looting and vandalism, it still felt opulent inside. Some bulky chandeliers and elaborate fretworks were the only removable, sellable objects that remained in place. A mix of grandiose murals and scrawling graffitis adorned the ceilings and the walls. The stairways had caved in, so we couldn’t access the upper floors.

We spent some time chilling on the rear porch, marveling at a superb view of the Euphrates River and the unending date-palm plantations along its shore, and moved on.

We drove further south to our last stop: a village called Al Kifl on the eastern bank of the Euphrates.

The village owes its name to the Muslim prophet Dhul-Kifl, who is thought to be the same as the Jewish prophet Ezekiel. Whatever his name, it is he who is believed to lie buried in that archaic tomb there situated. In fact, it may well be any random ancient dude with enough money to afford a little mausoleum. But that’s of no importance when faith is involved.

Clued by legend, medieval Jews associated that nameless grave with one of their great fabled oracles and thus turned it into one of Judaism’s holiest sites outside of Israel. Thousands of Jewish pilgrims flocked there annually for a thousand years until they recently stopped for obvious historic reasons.

Rather curiously, the monument was preserved in its authentic state throughout the 20th-century persecution of the Iraqi Jews. It was only after Saddam Hussein’s demise the authorities converted the synagogue into a mosque and replaced the Hebrew inscriptions with Koranic verses.

The venerated tomb’s conical dome was visible from the parking lot. A newer wall and a set of minarets, one leaning like Pisa’s tower, encircled it. A certain feel of austere sacredness pervaded the ambiance. We locked the car and proceeded to the gate.

Ibraheem had brought a headscarf for Sophie, mandatory to be allowed into the holy place. It was a nifty one, pink and white with ornate patterns, provided by his mom. But the guard at the entrance didn’t share her stylistic taste and instead supplied a black full-body cover.

Accompanied by a guy in a suit, we were then permitted to enter the premises. There was a nice courtyard with trees and arcades, a modern mosque with a couple of praying old men, and the poky burial chamber.

A coffin lay in the middle, enclosed within an elaborate wooden cage. A bulb of Islam’s characteristic green color within it gave the room a psychedelic glow. Arabic motifs were faintly discernible, and a sole Hebrew epitaph survived engraved on the frayed walls. A dwarf-sized, vintage chair hung in one corner for a reason our escort did not explain.

Having seen that, too, we went for a stroll in the village’s bazaar and drove away. We were back in Baghdad by early afternoon.