Notwithstanding the subtle mantle of high-hovering cirrus clouds that webbed the east, it was a brilliant morning. A soft quietude and a caressing breeze prevailed in the air.

A fat grey ox with erected horns was walking lazily along the sandy street below the rooftop I was drinking my coffee at. A slender woman covered with a filmy, pink scarf was hanging the laundry on a stretched cord some few rooftops away.

The massive central citadel and all the surrounding stone houses did really shine like gold in Jaisalmer: Rajasthan’s golden city. Clusters of eucalypti shaded the sparse house yards by the town’s verge. And beyond, there was only sand and rock. Out there, a vast land extended towards the distant horizon; a land occupied by Thar: the Great Indian Desert.

It was about 8:30 am when all was ready to venture out. All our supplies were loaded in the car. And I, my French companion, and our eagle-faced local driver were leaving the westernmost town of Rajasthan behind, heading further west.

For the most part, there was nothing but hot desolation out there. About 10 km after the town, we made our first stop at a rudimentary settlement named something like Mulchager. It consisted of about a dozen clay shacks, enclosed by a rectangular wall within an area no larger than 200 m2, amid boundless sand and parched shrubs.

Colorfully veiled women scurried busily up and down the place, performing various works. A few children followed us around with open palms, uttering “rupee rupee” between intervals of quiet staring. A bunch of men sat complacently around a table in the middle of the yard, drinking chai, smoking beedies, and checking us out curiously.

Our next stop came only a couple of km later: a gypsy encampment, where tents and sketchy stone shelters were loosely agglomerated within a large, open area. I found the people there much more amiable. A man squatted down on an unshaded spot, toilsomely breaking big rocks into smaller pieces. He greeted gently. Another man, further away, invited us for a cup of chai in his small yard. His English was surprisingly good. So we got to have a very interesting chat about their nomadic lifestyle, while his eight children hung around smiling shyly.

We moved on further. The sun had by then soared a good deal through the blurred blue sky. The heat would be inexorable were it not for the relieving breeze that blew above the bleak land, forcing sand granules to roam through the air, and putting in rhythmic motion an array of wind turbines atop the rocky hills we were driving by.

We drove some five km west, some five more on a dirt road leading south thereafter, and we arrived at the ruins of an abandoned village, called by our driver “the ghost village”. He narrated a story of a gorgeously beautiful daughter of that village’s chief who lived there some eight centuries ago…

A grand, wealthy Maharaja was dazzled by the young girl’s charms and demanded that she be sent to his harem. The father refused to let go of his beloved daughter. And instead, to avoid the consequences, together with the village’s entire population, they deserted their homes overnight and set off wandering around the world—perhaps, who knows, generations later, ending up in Europe to beget a portion of the modern-day European Gypsies.

The village was left to decay ever since. Rough desert shrubs occupied the interiors of the roofless walls of the erstwhile houses. Only a temple and a couple of other important, higher buildings have remained intact to remind that people had once thrived there. Only lizards and jackdaws now inhabit the place on a constant basis, cows and gypsies occasionally passing by… like that father-and-daughter gypsy duet we found squatting in a shady, narrow lane… the old man eager to play frisky tunes on his flute and the girl to wiggle her body sensually upon the reception of some copper.

Further south, we encountered an oasis. That little pond—no more than 30 meters from side to side—was the sole water source within a 30-km radius around it. Some kind of shrine stood on its shore; probably to please whatever sort of divine power responsible for that most valuable gift. A team of some 30–40 women carried sand and stones up a slope with large trays balanced on their heads, apparently working on some water-saving project, while a few men superintended the works, sitting and smoking phlegmatically under the wide foliage of an acacia.

We then visited an abandoned stronghold in yet another deserted village nearby, which was known as Khaba Fortress. The quiet there was profound. I saw nothing moving, except for a small squirrel carrying a twig in his mouth, who vanished in an instance, climbing up a wall as soon as he took notice of me, and a noble peacock, who all of a sudden appeared in front of me, walking clumsily yet illustriously as if to show off.

That was our last stop. We then drove straight for some 30–40 km until we reached the outskirts of a village named Khuri. That was as far as the road could lead us. We’d have to continue by other means onwards.

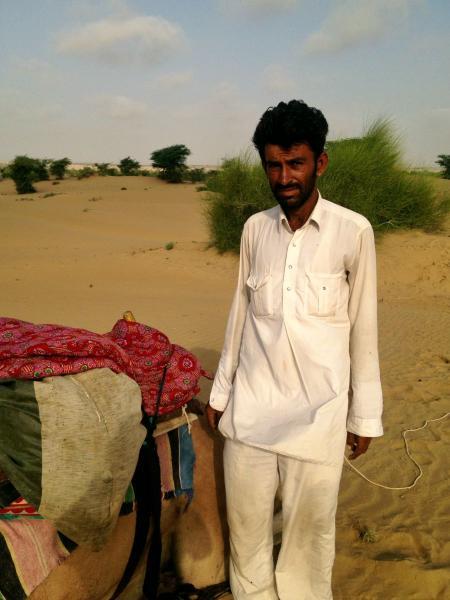

It was a bit past midday, and the sun had reached its zenith. We settled under a lone tree to wait for our guide to arrive with the camels. He was a young local villager. His real name was Anil but he preferred to be called Maharaj (Sanskrit for great king). He brought three camels, one female named Lakshi and two males named Disco and Michael Jackson.

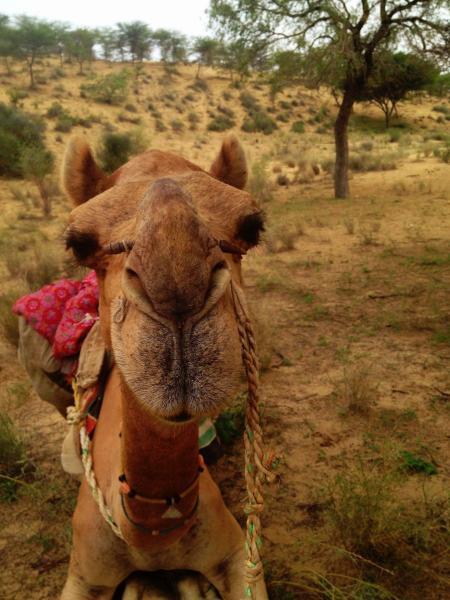

Disco, being apparently the weaker one, got burdened with the greatest bulk of the supplies. The other two would have to haul us together with some fewer things. We tied them all together in a caravan formation, the French guy rode Lakshi, I rode Micheal, everything was ready, and Maharaj set off striding ahead, leading our small camelcade into the desert.

Micheal Jackson raised his front legs to the point of kneeling; then lifted the rear portion of his body on his two-meter-tall hind legs. And finally, with a swift movement, he leaped on all four and started on a forward-moon-walking-like pace.

The desert noon was profoundly serene. Only sudden gusts—whipping the immense, flat, sandy landscape—and the occasional songs of the overflying birds would interrupt the silence discontinuously. That remained so until, a while later, that dull, faint metallic sound began to tinkle from behind.

I didn’t pay much attention to it at first, being aware of its presence but in a musing-minded state. Only after I consciously registered it for a cowbell approaching steadily closer, I turned my head back.

I saw a quadruped that resembled a camel in all but size, bearing a funny, erect tuft atop its hump, trotting ungainly to keep up. It was Lakshi’s calf, the baby camel; just two months old, fresh in life, but already as tall as me and quite heavier. He was to follow us for the rest of the trip.

At about 1:30 pm we stopped for lunch under the fair, relieving shade of a khejri tree (Prosopis Cineraria). Before doing anything else, we ridded the camels of their burden. Maharaj shackled their front legs with rope, reducing the length of their strides to some ten inches, and they were left to roam and graze freely.

Then we got to work on our own meal. We collected a few stones and firewood and lit a fire. We selected and chopped some vegetables from our provisions while Maharaj kneaded flour, water, salt, and a bit of oil into a dough for chapatis.

It was an exquisite lunch and an exhilarating digesting nap we had at that random piece of land within the Thar Desert. The day had progressed a good deal when Maharaj quit the comfort of the shade and set out to fetch back the camels, who meanwhile had wandered out of view.

While waiting for his return, I decided to go for a short stroll to a nearby dune. As soon as I reached the purview on its top, I found myself confronting a small gazelle some twenty meters away. She stared at me for a few seconds, and upon getting over her wonderment, she turned around in something less than an instant and fled, bouncing briskly towards other lands.

We rode the camels and advanced for some way further into the desert. Shortly before sunset, we were standing atop another tall dune. Amid the vast desert with its endless billowing dunes, there was a tiny cattle ranch down the valley to the east. I discerned a moving silhouette that I soon made out belonged to a young boy heading slowly towards our part.

He came to greet and offer a bottle of milk. After a cup of chai made with the boy’s contribution, a fat dinner, and the uplifting thrill one inevitably experiences upon witnessing such a magnificent desert sunset, it was time for bed—metaphorically, of course. We laid a rug each for a mattress on the sand, used another rug for a blanket, and fell supine under the boundless star-flooded sky overhead.

The first glimpses of dreams had just begun to override my wakeful consciousness when I realized that one of them—a strong wind hissing furiously and blowing ample loads of sand onto my face—was an actual, physical sensation.

I opened my eyes and saw a blacker than the sky, mushroom-shaped cloud heading straight towards us from the east, periodically releasing its wrath my means of electrostatic discharge, diffusing the night sky with light.

I had my small tent with me, and that was the only tent we had. We jumped up urgently, all three, and struggling a good deal against the sand-whipping wind, we managed to pitch it. We placed inside all our water-sensitive possessions and waited to get wet ourselves.

The wind’s fury grew steadily stronger. The cloud’s edge passed at nearly 90 degrees upon our heads. A few drops fell… And it just overtook us scratchingly.

One who hasn’t slept in the desert cannot conjecture how more delightful sleep can be. Feeling perfectly rested and having attended series upon series of pleasant dreams, I got up that morning as soon as the first dawn light hit against my eyelids. Simultaneously, various little birds began to chirp happily, flying zippily between the scarce trees.

We had a lovely breakfast, packed everything, and set off walking. Holding the reins of a camel each, our huge friends following promptly behind, we headed to the dune’s south base and a couple of kilometers into the valley thereafter until we reached a tiny clay farmhouse.

We tied the camels—or rather let them believe they were tied; throwing their reins over a bush does generally suffice to keep them in place—and proceeded into the hut’s yard, where an old lady welcomed us with a hot cup of chai.

I squatted among the pottery shreds that were scattered all over the yard and focused on my steaming cup and fuming cigarette. A whole gang of children assembled around us for a shy nosey. An inquisitive yeanling kept hanging about the yard entrance, exhibiting a clear intention to jaunt in. But one of the little girls stood guard by the gate and rebuffed each of its attempts to enter.

Thanking for the hospitality, we stood up and egressed. Then was the time I got to ride a camel independently for the first time in my life. Maharaj taught me the relevant commands and operations, and we were good to move on. In response to a soft heel kick on his belly, Micheal Jackson leaped to his feet and marched forward without delay.

I found Michael a very cooperative camel. I could very easily direct him with the slightest twitch on the reins. Upon hearing that “toot-toot” sound I learned to produce by slapping my tongue against the hard palate of my mouth, he would amenably accelerate. And without needing to touch him at all, only lifting the withe and swaying it a couple of times through the air, he would gallop ahead spryly, my bum jouncing wildly up to half a meter over the saddle.

“Jiuuu!” I shouted, pulling his neck back slightly at the same time, for him to kneel compliantly and let me alight. It was lunch time. There was a 4-m2 thatch shed fixed on four thick branches pegged into the sand. A plastic bottle hanging by a cord from one of the poles produced the only sound to be heard as the breeze sent it bumping rhythmically against the wood. A man sat there, apparently an acquaintance of Maharaj, and had some food prepared for us already.

After that filling meal and a revitilizing desert siesta, it was time to bid farewell to our French companion. He would head back to town accompanied by that man. Maharaj and I were to venture further deep into the desert.

We proceeded on foot for the rest of the day. We made a stop at another shack for a cup of chai. An old man sat by the entrance, smoking one beedi after another. A little girl was crouched down some distance away from us, washing dishes with sand instead of a sponge.

Sunset was imminent by the time we made it to the top of that dune we intended to spend the night. Before anything else, I went on a brief excursion around the area and found a great spot to enjoy the sunset from.

I shared that with a fox I sighted some 30–40 meters away. She was moving slowly and stealthily, with great caution, facing always the opposite way from me. It seemed as though she was after a candidate dinner but was then forgetting about it at intervals to stop and wonder at the beauty of the descending sun. That was so until I decided to make her aware of my presence with a loud whistling. She swiveled her neck towards me instantaneously, regarded me bewilderedly for a few moments, and ran away like crazy, disappearing from my view in a matter of seconds.

The following morning was one of glorious placidity. The sky seemed as transparent as nothingness, and the sun, a perfectly rounded fire sphere, was slowly rising through it.

A herd of cows moved slowly across the valley, munching whatever grass was to be found along the way. A flustered calf was running around as if possessed, crashing against the rest. A fat collared dove passed low above the dune, screeching out his “kookookoo” calls while speedily approaching his mates in the distance. A daw landed sneakily near our food sack and began to skirt it circumspectively. A cloudy swarm of louse flies ailed poor Lakshi who sat nearby growling and suffering her nemesis. Dung beetles came and went, carrying away the products of her excretion.

We spent the rest of that day no differently than the previous ones: wandering around the desert. I got to ride Lakshi that day. I didn’t find her a particularly obedient camel compared to Micheal Jackson. She basically didn’t give a shit about my will. I never managed to make her run. I even tried to kick and whip her, but she’d only maintain the same pace stoically. When the baby camel positioned himself ahead of us, she wouldn’t listen to anything but only follow him blindly.

We ended up on the top of a new dune, where we camped for the last night of the trip. We garnished our dinner with some fresh mushrooms Maharaj had found earlier in the bush. And then we smoked a bit of opium and stayed up till late, staring alternately between the comforting fire and the overwhelming firmament, giving an audience to the heavy silence.

Last day in the desert, we woke up early, had breakfast, and started on our way back to Khuri village. About halfway thither, we stopped for lunch at a friend’s of Maharaj. He maintained a small fenced farm amid the enveloping desolation. It covered an area no larger than 250 m2 and yielded lentils, wheat, and watermelons. He kept a minimal, makeshift straw shed for refuge during the day’s hottest hours. That’s exactly where we settled and started preparing our meal.

There was a flask of whiskey I’d been carrying with me throughout the trip, but I hadn’t yet touched it as Maharaj didn’t drink at all, and I didn’t feel like emptying the whole thing by myself. That old guy over there, however, proved an avid drinker. He was also a very interesting talking companion. His English was excellent. He used to work as a tourist guide in the desert for 35 whole years before he decided to retire and create this small farm to live in peace through his old age. We talked about lots of curious topics, such as gazelle hunting and illegal opium cultivation in the region, until we depleted the flask and surrendered both to a refreshing siesta.

By the time I opened my eyes, Maharaj had already packed and fetched the camels. A couple of hours later, we were waiting by the side of that lonesome road outside the village. After a while longer, that same eagle-faced driver had shown up and we were driving back towards civilization.

Photos

View (and if you want use) all my photographs from the Thar Desert.

Maharaj, or Anil – as his real name is – is a man of 29 years of age from Khuri village. He has been working as a desert guide since the age of 13, having led multitudes of people through the Thar desert. His English is very decent (in fact much better than most of the agency spokesmen you find in Jaisalmer). He bears quite a volume of knowledge concerning the desert, its peoples, and its ecosystem. He is a genuinely honest and kind man – something very rare, I found, with people working with tourists in this country. He is the father of three school-aged children, whom he supports by the means of two cows and two goats he maintains at his village and his guiding job. He mainly works for one company, being paid scantily in proportion to what those people usually make out of tourists – which, I witnessed, might be outrageous. He may well help anybody in arranging a more independent desert tour with fewer costs – excluding the useless intermediary agencies. I would like herewith to recommend him unreservedly to anybody who may be contemplating a tour in the Thar Desert. +91 (0)9929720636 is his private telephone number.

Accommodation and Activities in India

Stay22 is a handy tool that lets you search for and compare stays and experiences across multiple platforms on the same neat, interactive map. Hover over the listings to see the details. Click on the top-right settings icon to adjust your preferences; switch between hotels, experiences, or restaurants; and activate clever map overlays displaying information like transit lines or concentrations of sights. Click on the Show List button for the listings to appear in a list format. Booking via this map, I will be earning a small cut of the platform's profit without you being charged any extra penny. You will be thus greatly helping me to maintain and keep enriching this website. Thanks!