We were very lucky it was overcast over the city of Erbil. That’s not a common occurrence. And it happened on the perfect day: the day we had to spend in its entirety dawdling outside.

Erbil isn’t a city with vast forested parks full of shaded benches. It is a city with broad streets and empty lots, interspersed by sparse, glass and concrete vertical surfaces. We would have fried like shrimps under the common sunny conditions.

We had a late flight and had to leave our accommodation early. Our destination was to be Iraq’s capital, Baghdad. Flying and getting a visa on arrival at the airport was the only way we found to be permitted into the Arab part of the country.

The streets of Erbil’s Naz City suburb were still vacant and quiet. We occupied the first table of the first-to-open breakfast place and lounged there over two cups of the cheapest coffee, while all the rest of the tables were constantly engaged by big, affluent local companies who each feasted on what amounted to half the restaurant’s gaudy staff’s daily wages.

A few hours of aimless ambulation and a quick meal of the cheapest kind later, we ended up in what most closely resembled a park within the district. It was a narrow strip of grassed ground, bordered by an expressway on the one side and a cluster of workshops on the other, with a path and a few benches amid the litter; a decent place to kill some time reading.

Then came another coffee, another meal, and plenty of more walking. And when darkness fell, it was time to head to the airport.

This story is an excerpt from my book "Backpacking Iraq", wherein I recount my journey through this misunderstood and fascinating country. The entire book is available to read online for free. But if you'd like to get it on your e-reader or as physical copy (and, doing so, support my creative activity), you may check it out on Amazon.

The good thing was that we were within walking distance from it; the bad one that, for security reasons, they presumably wouldn’t allow us to enter its premises on foot. We began striding towards it anyway, to find out whether that was the case indeed.

Sure enough, our progress was hampered at the first checkpoint. But to our convenience, instead of forcing us into a taxi, the guards asked some other passengers to give us a free ride to the departure hall.

Repeated controls and security procedures consumed most of our pre-flight time. So we waited little before boarding the aircraft.

I’m not the guy who will post a Facebook airport check-in update and take ten pictures out of every airplane window. The only notable entertainment I find on a plane is reading and eating during breaks from sleeping. In fact, flying often affects me just like barbitals. But about this flight, I was rather excited…

Upon approaching Baghdad’s runways, it is a common practice for pilots to perform the so-called corkscrew landing. In short and as I understand it, this special maneuver involves an abrupt, spiraling descent aimed to minimize the risk of the craft’s course coinciding with the one of some hostile, explosive projectile. It sounded as terrifying as fun. To my ultimate disappointment, however, it never happened.

Instead, the plane glided at such a height above the rooftops that human silhouettes were discernible on them for some fifteen minutes before touching the ground. I believe even I would be capable of bringing the thing down, trying for the first time my hand at a bazooka. Fortunately, no more-experienced hand happened to have a go that night. And so we landed safely at the formerly known as Saddam’s, Baghdad’s International Airport around midnight.

Our steps concluded before the immigration control. A bunch of other foreigners hung around beside a little desk in the hall’s far corner. There appeared the mustached and shined-shoed officer to whom we gave our passports for him to give us each a long form to fill. He impatiently beckoned us to hurry while we were at it, at last coming over and snatching the papers half-filled out of our hands, mumbling in broken English “only name, only name”.

We then took a seat and waited for around an hour awake and maybe as long asleep before he returned. We bartered $80 for our stamped passports and were welcome in the Arab Republic of Iraq.

Accommodation in Iraq isn’t cheap, whatever you compare it to. We wouldn’t pay a full day’s rate for a couple of hours. The arrival hall was roomy and cozy. There were some nice and calm spots where we’d have crashed snugly until dawn if we weren’t locked out.

We made the mistake of going past the automatic gates for a smoke. None of them proved to open the other way. We walked back and forth the entire facade a few times, asking, but nobody delivered any intelligible communication except an arm pointing in any direction.

At least it was warm outside—not like that time I was kicked out in summer clothes from a closing-overnight, random Norwegian airport in September and almost froze to death, huddling and trembling under a ramp in the parking lot. Here in Baghdad, at one end of the building, away from the crowd in the vintage chauffer attires and their lined-up cabs, we found a comfy row of cushioned seats, just long enough to prostrate at full length.

I have the impression that the Pakistani working chaps, who took a shift at daybreak and were the seats’ rightful occupants, weren’t as happy about us sleeping there. I bear faint memories of them murmuring in the twilight over my snoozing brain. It was about time they eventually woke us up; time to get going.

My aforementioned brain isn’t good at stopping to snooze without a generous dose of caffeine, and there was no such thing to be found around. That made our get going all the harder, which already wasn’t as simple as leaving an airport ought to be.

The site looked more like a prison or a gold depository. The military posts were denser and more heavily armed than in Erbil. Here, too, pedestrians weren’t supposed to be moving in and out of the airport, but unlike Erbil, neither were private vehicles. Moreover, the 12-km distance between the terminal and the outer gate rendered the prospect of giving it a go anyway a little daunting. But the taxi fare was ridiculously expensive…

While examining a tall and long concrete wall we’d otherwise have to circumvent for potential shortcuts, a series of horn beeps resounded from behind our backs. They were produced by a dude in a white shirt and a blue chauffer hat in the driver’s seat of an empty van.

The frequency of English words in his speech was as high as 5%, so we could understand him somewhat better than anyone we had so far spoken with. He seemed legit, and we trusted in him saying that there was no chance we could leave on foot, and our best option was to go with him for a 6,000-Iraqi-dinars worth of a ticket. He even treated us to drinks and snacks on the way.

When he dropped us off, past the final checkpoint, he took it for his mission to ensure we’ll reach our hotel securely. He stepped out, hailed the first taxi, photographed its plates, arranged a price with its driver, and gave him a barrage of Arabic instructions that sounded a tone overzealous. I wasn’t anyway worried to any degree about that driver posing a danger. Though not exemplarily friendly, he was old and beyond doubt innocuous; looking incapable of moving his body in ways considerably more complex than the ones required to drive the car.

With curiosity hitting red, I was gaping at the peculiarities of our novel environs as we progressed bumper-to-bumper through Baghdad’s chaotic traffic. This was the first time in my life I was observing such a thoroughly integrated hybrid of a city with a military base.

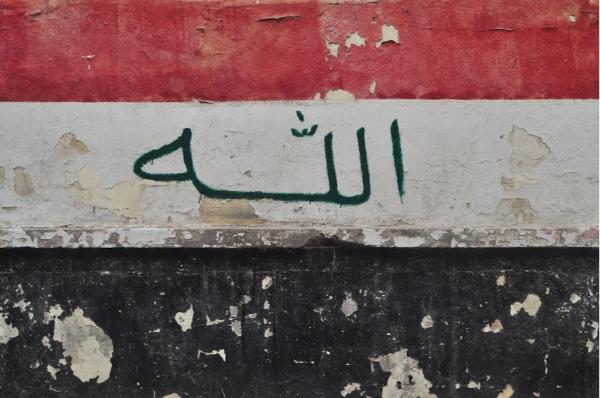

The stretches of barbed wire were as pervasive as cycling lanes are in Copenhagen. Every major junction featured barricaded, elevated emplacements with big, stern gun barrels sticking out from piled sandbags. The armed and uniformed population wasn’t a minority to the civilian one by too great a margin. Flags of a myriad bombastic designs wavered all over the place.

We got off the car at the point we became sure we had driven far past our hotel, paid 20,000 dinars for the ride, and began walking back.

At the corner beside the hotel’s entrance, there was a street-food stall adjoined by a couple of plastic tables on the pavement. The two men who lazed at them invited us for a cup of tea, in a manner so cordial that we couldn’t decline. Then they got entangled in a genial argument about who is going to pay for our drinks, so that the loser ended up buying us sandwiches. That was but a mere introduction to the astounding hospitality we were to experience in this troubled but gracious city.

The hotel felt like the stage of some period film set in the British Middle East; the sort of place you’d walk in with a fedora and a suitcase on either hand during a break from a ride on the Orient Express. The lobby’s ceiling rose for two full stories and was adorned with a bulky, sparkling chandelier. A perimetric interior balcony with wooden balustrades stood above and led to the rooms. Various vintage pieces of furniture and ornaments lay around.

All the staff were really nice and helpful, and a few spoke good English. There was that one guy who also did that in a British accent—“Every day same shit” was his motto—I sort of regret I missed the chance to get to know him better. He invited me one evening to smoke a joint with him after his shift, but that was a few hours away, and my tiredness wouldn’t sustain the wait.

After an express shower and essential rest, we were out in the streets, thrilled to explore.

We would later be told that the district we stayed in was far from famed as one of the city’s safest. Regardless, I felt comfortable during all—or most—times.

Civilians greeted us with smiles and kind words. Many stepped forward to pose for pictures. Soldiers were scarcer and discreetly curious. The traffic was dense and tricky to meander through.

Our first stop was an ATM where we withdrew money watched by two guards with machine guns and bulletproof vests. Then our steps led us to an immense park on the east bank of the Tigris. It must have once been a public park; a long-shut restaurant and dilapidated playgrounds hinted that. Now the army occupied half of it and junkies the other.

Access to the part under the army’s jurisdiction, which was the entire riverbank, was prohibited. I found that out when a soldier appeared out of nowhere and prevented me from stepping over a restriction tape. Photographing was also forbidden. That I found out when, despite being sneaky, a soldier again saw me taking a picture of an armored vehicle and forced me to delete it on the spot under threat of confiscation. This attitude made better sense to me when, some weeks later, an assassination attempt was made against the country’s Prime Minister by three drones flying across the river loaded with explosives.

Finding no adequate entertainment in this park, we retraced our steps back to residential quarters. Reaching the first adjacent street, we were stopped by an odd, but otherwise alright, old creep who proposed us to come to his place to show us his bed, or something along these lines.

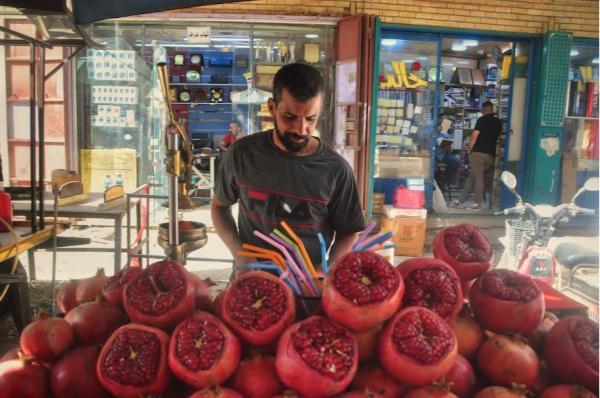

A few strides down the pavement, a young driver braked in the middle of the street, a queue forming rapidly behind him, and called to us, his joy-radiating face stretched out of the window. He was a political science student, eager to practice his English. We followed his prompt to enter the car and—to the concatenated drivers’ relief—we drove to a nearby place where he treated us to a juice and an interesting talk.

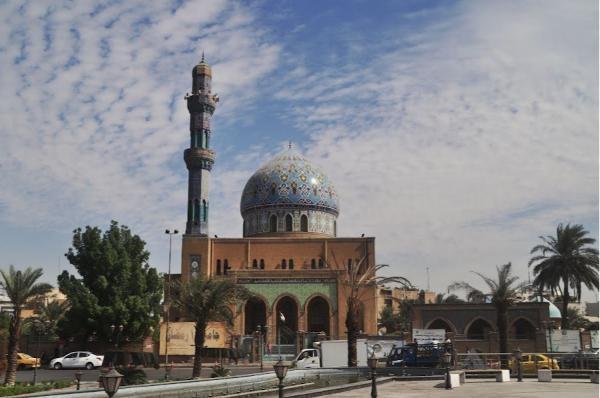

Thanking and goodbyeing him, we made our way to one of Baghdad’s bridges and began our way across the wide river. People in passing cars cheered and honked at us enthusiastically. A pleasant afternoon breeze blew and perturbed the surface of that river that has nurtured numberless generations of diverse civilizations. A thousand minarets towered above the skylines on either side.

The city was strikingly different on the Tigris’s west bank. The country’s administrative functions were concentrated there: a cornucopia of ministries and public offices of very imaginative sorts, seemingly established for funneling public funds to their establishers’ pockets.

All these were fortified with gargantuan walls, omnipresent security cameras, tanks and heavy artillery, and oodles of mustached versions of Rambo. Broad, dusty streets without sidewalks, let alone pedestrian crossings and traffic lights, communicated between them. Foot traffic was rare in that area, to begin with. Now, when that traffic involved two lone, weary travelers, one female and blond, with cameras hanging from their necks… imagine the shock on the witnessing soldiers’ faces.

They literally stopped us at every crossroad. They would each time control our passports, and then detain us a little longer for their recreation’s sake, before letting us go, warning against taking pictures. In response, I was especially cautious when using the camera.

Having described a long circle, we crossed another bridge to our side of the river and returned home for some rest before the evening. We started this with a walk around the neighborhood, had a meal in a fast-food place, chattered with various merry locals, and got into a taxi.

We were going to meet two local friends, Ali and Ahmed, for a cup of tea. The city was in exceptional turmoil that night. Some dudes—I think of a militia faction puppeteered by Iran—were lamenting the results of the recent election by carrying out an armed protest in the streets. The holders of the official government’s weapons were reacting by tightening controls, blockading streets, flying helicopters at minaciously low courses, and letting loose armored vehicles instructed to not turn off their strident sirens for a moment.

Our appointment was at a cute teahouse with outdoor sitting space by the riverbank. It was a popular place, packed with jolly companies of tea-drinkers and shisha-smokers and lined-up fishermen waiting nonchalantly for a bite along the murky waterfront. It may have been the last free table we sat at.

After a few teacups and plenty of interesting conversations, we stood up to leave. But that didn’t prove easy… In a frenzy of excitement, one company after the other called us over to their tables for pictures. Then I got dragged by some staff into the kitchen. They all neglected their jobs to take selfies with me and laugh their heads off as if there was no tomorrow. I felt kind of grateful when a furious boss invaded, screaming things whose meaning I better not guess, and presented me with the opportunity to sneak out.

It was nearing midnight while our friends drove us back to our hotel through the now desolate streets, habitually turning on the car’s interior light for the soldiers to look inside at every checkpoint. They also gave us lots of recommendations for places to visit along the way before they dropped us off in front of our entrance.

We were up by dawn the next day to go on a day trip to ancient Babylon and a couple more historic sites in Baghdad’s vicinity. But this is going to be the subject of another story, as this one’s already getting long enough.

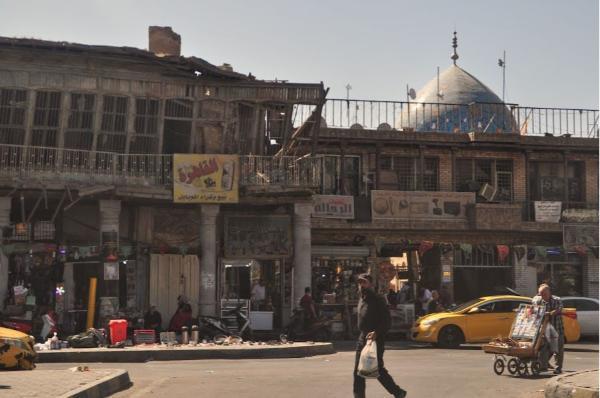

Fast-forward twenty-four hours, we devoted our last full day in Baghdad to full-day exploration. We left home early and set route towards the old town. We briskly meandered through the crammed stalls and the ever-fluctuating throng of humans, carts, and horses that was squeezed between the buildings and the eight-or-so lanes of stranded automobiles in Al-Khulafaa Street.

The noise was insane. On top of a constant engine-buzzing background, boomed a cacophony of horns, sirens, shouts, neighs, helicopters, and a stupefying amplitude of vibration frequencies that diffused through the air in perfect chaos. And then everything was transiently stifled at prayer time by the imam’s devout call climbing in rapture up a scale and piercing the sky and souls with existential terror.

People we crossed paths with were again congenial to such a degree that makes one happy and proud to be a human. A soldier could not hide his merriment while trying to seriously request us to get off that restricted pedestrian overpass we climbed to take a picture of the street.

We ended up sitting on a tiny bench, in the arcaded sidewalk of a narrow street, sipping a cup of tea and people-watching from a low angle. Folks were in steady flux. Most of them kept their neck turned back at us, still dumbfounded, for quite a distance after going past. A senile fellow on the next bench was in a deep trance, periodically lifting with great effort the mouthpiece of his hookah for a drag. A little-mental bloke on the opposite bench was staring us out intently yet apathetically.

Later, in a tight, arched bazaar, we ran into those two Iraqi-British chaps, whom we first met the other day in the junkie park. They were nice guys, and we gladly accepted their invitation to some famous traditional teahouse.

It felt grand yet homely. As the custom goes with such hangouts, its walls were full of pictures of noted denizens and visitors. It was a foreigner stomping ground, too. I saw in there more of them than in the entire city combined. Some Iraqi-American guys talked to us from around the corner; a British Youtuber materialized at the door, selfie-stick, big fluffy microphone and all; another group of travelers followed. We soon were all a big company; all but the dudes who sat in the corner…

They were sinewy, looked busy and American, wore sunglasses and spiral-cabled earpieces. CIA or something of the sort, I thought. Something interesting is going to happen here…

It wasn’t an assassination or anything too action-like. It turned out the US ambassador would pay an honor visit for that historic cafe’s renovation following a terrorist bomb attack it’d suffered some years ago. More agents appeared and got deployed inside the lounge and along its outer walls. Then showed up that tall, white-haired man with his entourage of a camera crew and I don’t know what else. He sat at different tables, shook various hands, produced plenty of stagy smiles for the TV and the papers, and departed.

Having got a toothache from the many sugary cups of tea, we continued our stroll. We crossed two new bridges back-and-forth on a new excursion to the west bank. Late afternoon, feet almost-blistered, we were getting close to home. But then the army stopped us.

I didn’t notice them while I sauntered in the middle of the street, thoughtlessly recording video… They fixed two stools, sat us down by the roadside, offered us consecutive glasses of fresh juice… and patently amused, requested us to wait…

An hour later—I was getting impatient—the captain received a stimulating radio call. He put on his helmet, straightened his vest, wiped his boots—I didn’t see that, but I’m pretty sure he must have also adjusted his mustache—and stood in testy expectation until his superior arrived.

Although in a civilian outfit of an authority-denoting cut, he was younger and smaller than his inferior. So he had to try extra-hard to look tough. And he managed well. With a slamming boot and a puffed chest, our guy saluted him reverently before beckoning us to come over.

He hard-nosedly asked us what we were taking pictures of; to which we replied “walls, cars, the sky, nothing much, tourists”. He only asked us to put the cameras in our bags and had us discharged. That’s what we waited all this time for.

We only retrieved the cameras after turning around the next corner. Now we were in our neighborhood’s crummy backstreets. It indeed felt kind of dodgier in there than on the main roads. Swarms of poorer locals and Sudanese immigrants filled the area. They were friendly, with a few exceptions of men glowering at us discontentedly or telling us off for taking pictures. At one point, we became enmeshed among an unruly mob of too-excited-to-see-us youngsters. Producing a wild babel, they almost-literally dragged us around for successive selfies. At last, we broke free after a passing cop’s intervention and made it back to the hotel.

We didn’t even have enough time to shower and change—well, we had nothing to change to, anyway—but what I want to say is that we left again immediately. Ahmed, from the other night, came and picked us up for a night ride.

We first went to one of the higher-end districts. Arrays of modern restaurants and teashops clustered along that bank of the Tigris. They were all flooded by progressive youth. Yet more companies formed along a ledge at the riverfront, conversing ardently around hookahs, overlooking a distant, green-lit bridge in sharp contrast to the dim city and the black river. We had food and pudding, walked around a bit, and then drove to a liquor store by the junkie park.

It was one of many around the city. They all had a steady, round-the-clock stream of customers, often parking a distance away and proceeding to the counter on foot, surreptitiously and conspiratorially. The merchandise was fairly diverse and cheap for Arabic standards.

Two ghost-like, black-veiled girls hung out on the gloomy curb near the store.

“They were prostitutes,” said Ahmed after we left with our drinks.

“Oh, really?” I responded, genuinely surprised.

“But of course, it’s obvious!” he retorted, turning at me a stunned face that would befit more a line like “but of course the sun shines”…

Well, okay… As far as I’m to judge, I know of knee-top heeled boots and net leggings and such, but that a human lies within is the only thing I can deduce by any reasonable degree of obviousness when I see a burqa… But when you give it some more thought, the liquor store definitely makes for a strategic post.

We settled on a ledge at the park’s edge, facing a faintly and orangely lit street used only by sporadic army and police vehicles. A bunch of lads were also drinking beside us. A few strange characters loitered about. An intoxicated, decrepit loony approached us, telling stuff, but those other guys ousted him. They said he was too crazy to predict.

Beggars, mostly old women, were reaching us in turns. With one of them, I had to lock my arms behind my back to refuse that baby she was trying to force onto my lap—not that I have anything against babies in general, but ending up responsible for a newly orphaned one of them wasn’t something I fancied for my last night in Baghdad.

A convoy of military lorries barreled down the street, packed with equipped soldiers, their sirens screeched madly. One lad jumped forthwith behind the ledge and remained hidden until long after the convoy’s tale had passed. It looked as suspicious to me as it sounds to you… He explained that the commander of that unit was his father… In no country, let alone a Muslim one, does the son of a man of discipline wish to be seen getting drunk at night in disreputable parks.

Having finished our drinks, we returned home. We went to bed late that night and got up early. We were going to catch a minibus to Mosul.

Photos

View (and if you want use) all my photographs from Baghdad.